Introduction

Since its emergence as a global pandemic in March 2020, COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has significantly strained healthcare systems worldwide.1 In the United States alone, the National Health Expenditure reported a staggering 9.7% growth, reaching $4.1 trillion in healthcare spending in 2020, despite an estimated one million COVID-19 related deaths.2 Cardiovascular complications, including myocarditis, pericarditis, arrhythmias, acute coronary syndrome, thromboembolic events, and sudden cardiac death, were major contributors to this mortality. Myocarditis, inflammation of the heart muscle, has been observed in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence rates of 0.146% in hospitalized or hospital-based outpatient settings, significantly higher than the 0.009% in non-COVID-19 patients.3 , 4 Furthermore, the approval of mRNA COVID-19 vaccines in December 2020 brought attention to a potential, albeit generally mild, risk of vaccine-related myocarditis.5 The exact mechanisms of COVID-19 myocarditis remain under investigation, with hypotheses pointing towards widespread inflammation, cytokine toxicity, and direct viral injury to the heart muscle.6 Many clinical uncertainties persist regarding optimal hospitalization strategies, levels of care, the necessity of ischemic evaluations, and transfers to specialized facilities for patients with COVID-19-associated myocarditis. Current research, beyond limited case reports and small observational studies, provides insufficient data on the clinical course and outcomes of this condition. This study leverages the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database to comprehensively evaluate in-hospital outcomes, rates of angiography, hospital stay durations, and total hospitalization costs for patients diagnosed with COVID-19-related myocarditis. For those interested in related fields such as medical coding, particularly in regions like Vijayawada, understanding the complexities of disease coding and outcomes is crucial, although this study focuses on clinical outcomes rather than coding practices, such as those potentially encountered with services like pi care medical coding vijayawada.

Methods

This research utilized the 2020 NIS database, a component of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.7 The NIS database is a robust resource, encompassing approximately 95% of the U.S. population and containing 20% of discharge data from nearly 1,000 hospitals. Rigorous annual quality assessments validate its internal consistency. As the NIS database contains de-identified, publicly available data, Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study.

COVID-19 cases were identified using the International Classification of Disease, Tenth Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) code “U07.1,” the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-approved identifier within HCUP. Patients were then categorized into cohorts with and without myocarditis based on specific ICD-10-CM codes (detailed in Supplementary Table 1). Comorbidities were assessed using the Elixhauser comorbidity index provided by HCUP, with a more detailed list in Supplementary Table 2.

The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality. Secondary outcomes included acute kidney injury (AKI), heart failure (HF), stroke, cardiogenic shock (CS), sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), and mechanical circulatory support (MCS) – encompassing durable left ventricular assist devices, percutaneous ventricular assist devices, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events (MACCEs), a composite outcome of in-hospital death, CS, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke, were also evaluated. Furthermore, the study examined the utilization of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and angiography. Hospitalization metrics, including length of stay (LOS) and adjusted total charges ($), were compared between COVID-19 patients with and without myocarditis. ICD-10 codes for primary and secondary outcomes are available in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2.

Categorical variables are presented as numbers and percentages and compared using the Pearson chi-square test. Continuous variables are presented as weighted means with standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data, or median with interquartile ranges for non-normally distributed data, and were compared using independent t-tests. Unadjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using the Pearson chi-square test/linear regression, while adjusted ORs were derived from multivariate regression analysis. Variables used in multivariate regression are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Propensity score matching 2, employing near-neighbor and multiple inverse probability matching, was used to control for confounders and effect modifiers. Coefficients and matching variables for propensity score matching 2 are detailed in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, respectively. All analyses adhered to HCUP guidelines for stratification, clustering, and weighting samples.8 Discharge weights from NIS were applied to ensure national representativeness. Statistical analysis was performed using Stata Statistical Software: Release 17 (2021, StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas).9

Results

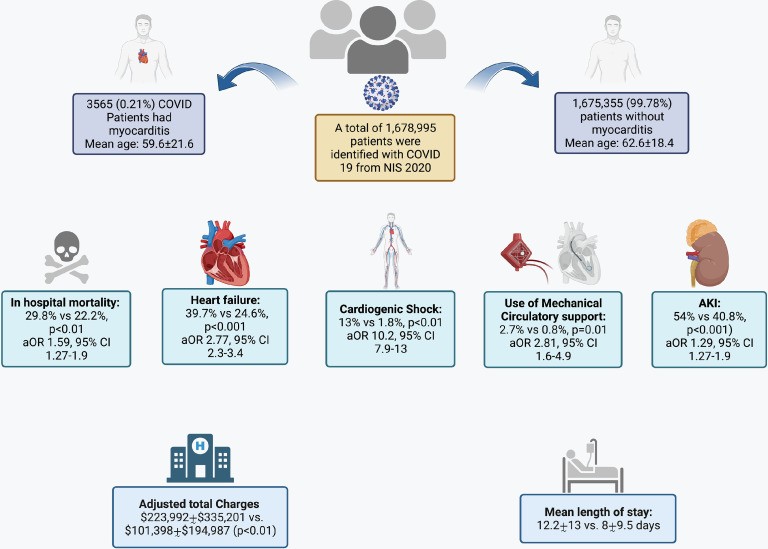

The analysis identified 1,678,995 weighted hospitalizations for COVID-19 in 2020. Among these, 3,565 (0.21%) were associated with myocarditis. Patients with COVID-19 and myocarditis were younger (mean age 59.6 ± 21.6 years vs. 62.6 ± 18.4 years), more likely to be male (59.9% vs. 52%), and more frequently identified as non-White (54.3% vs. 47%) compared to those without myocarditis. The most prevalent comorbidities in both groups were fluid and electrolyte imbalance (67% vs. 50%), cardiac arrhythmias (43.9% vs. 24.5%), hyperlipidemia (38.6% vs. 39.2%), and complicated diabetes (29.9% vs. 26.1%). Detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1, and a comparison of comorbidity proportions is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Table 1.

Comparing percentages of co-morbidities among myocarditis and nonmyocarditis groups of the baseline COVID-19 population

| Analyte | COVID19 without Myocarditis n = 1,675,355 (99.78%) | COVID19 with Myocarditis n = 3,565 (0.21%) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (years) | 62.6±18.4 | 59.6±21.6 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 871,270 (52%) | 2,135.00 (59.9%) | |

| Female | 804,085 (48%) | 1,430.00 (40.1%) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 824,200 (53%) | 1,525.00 (45.7%) | |

| Black | 309,915.10 (19.90%) | 865.00 (25.9%) | |

| Hispanic | 352,665.00 (22.70%) | 780.00 (23.40%) | |

| Asian/PI | 52,700 (3.40%) | 135.00 (4.00%) | |

| Native Americans | 16,734.90 (1.10%) | 30 (0.9%) | |

| Payer type | 0.46 | ||

| Medicare | 838,739.90 (52.50%) | 1,705.00 (50.40%) | |

| Medicaid | 252,154.90 (15.80%) | 610.00 (18.00%) | |

| Private | 440,505.10 (27.60%) | 910 (26.9%) | |

| Self-pay | 62,895.10 (3.90%) | 145 (4.3%) | |

| No charge | 4,490.00 (0.30%) | 15 (0.4%) | |

| Elective | 0.06 | ||

| Non-elective | 1596,919.90 (95.40%) | 3,455 (96.90%) | |

| Elective | 77,070.10 (4.60%) | 110 (3.1%) | |

| Hospital bed size (values vary by region & control) | |||

| Small | 406,509.80 (24.30%) | 615 (17.3%) | |

| Medium | 484,799.70 (28.90%) | 1,115 (31.30%) | |

| Large | 784,120.50 (46.80%) | 1,835 (31.30%) | |

| Hospital location & teaching status | |||

| Rural | 162,780.60 (9.70%) | 235 (6.6%) | |

| Urban nonteaching | 309,810.00 (18.50%) | 490 (13.7%) | |

| Urban teaching | 1202,839.40 (71.80%) | 2,840 (79.70%) | |

| Hospital region | |||

| Northeast | 307,579.70 (18.40%) | 985 (27.6%) | |

| Midwest | 372,855.20 (22.30%) | 840 (23.6%) | |

| South | 688,970.90 (41.10%) | 1,205 (33.80%) | |

| West | 306,024.10 (18.30%) | 535 (15%) | |

| Transferred in | |||

| Not transferred | 1,429,305.10 (85.80%) | 2,745 (77.20%) | |

| Transferred | 123,149.90 (7.40%) | 490 (13.8%) | |

| 114,015.00 (6.80%) | 320 (9%) | ||

| Transfer out indicator | 0.09 | ||

| Not a transfer | 1,316,650.00 (78.60%) | 2,790 (78.40%) | |

| Transferred out to a different acute care hospital | 50,350.10 (3.00%) | 155 (4.4%) | |

| Transferred out to another type of health facility | 307,259.90 (18.40%) | 615 (17.3%) | |

| Weekend admission | 0.4 | ||

| Mon–Fri | 1,241,795 (74.10%) | 2,590 (72.70%) | |

| Sat/sun | 433,635(25.90%) | 975 (27.3%) | |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Hyperlipidemia | 657,424.90 (39.20%) | 1,375 (38.60%) | 0.74 |

| Obesity | 438,549.90 (26.20%) | 905 (25.4%) | 0.62 |

| Smoker | 354,289.90 (21.10%) | 560 (15.7%) | |

| Prior CABG | 57,605 (3.40%) | 125 (3.5%) | 0.92 |

| Prior MI | 68,885 (4.10%) | 185 (5.2%) | 0.17 |

| Prior PCI | 67,475 (4.00%) | 170 (4.8%) | 0.31 |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 410,214.90 (24.50%) | 1,565 (43.90%) | |

| Hypertension uncomplicated | 632,300.10 (37.70%) | 920 (25.8%) | |

| Other neurological disorders | 287,169.90 (17.10%) | 860 (24.1%) | |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 366,919.90 (21.90%) | 725 (20.3%) | 0.32 |

| Diabetes uncomplicated | 245,050.10 (14.60%) | 355 (10%) | |

| Diabetes complicated | 436,450 (26.10%) | 1,065 (29.90%) | 0.03 |

| Hypothyroidism | 218,820 (13.10%) | 360 (10.1%) | 0.02 |

| Renal failure | 348,299.90 (20.80%) | 920 (25.8%) | |

| Liver disease | 90,735 (5.40%) | 370 (10.4%) | |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 5,270 (0.30%) | 20 (0.6%) | 0.24 |

| AIDS/HIV | 4,390 (0.30%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Lymphoma | 13,150 (0.80%) | 25 (0.7%) | 0.8 |

| Metastatic cancer | 18,560 (1.1%) | 25 (0.7%) | 0.3 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 41,120 (2.50%) | 60 (1.7%) | 0.18 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular | 49,890 (3.00%) | 245 (6.9%) | |

| Coagulopathy | 202,719.90 (12.10%) | 920 (25.8%) | |

| Weight loss | 131,009.90 (7.80%) | 420 (11.8%) | |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 839,499.80 (50.10%) | 2,415 (67%) | |

| Blood loss anemia | 7,595.00 (0.50%) | 30 (0.8%) | 0.12 |

| Deficiency anemia | 64,420 (3.80%) | 160 (4.5%) | 0.37 |

| Alcohol abuse | 44,455 (2.70%) | 115 (3.2%) | 0.34 |

| Drug abuse | 43,450 (2.60%) | 70 (2%) | 0.29 |

| Psychoses | 43,005 (2.60%) | 65 (1.8%) |

AIDS = acquired immune deficiency syndrome; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; MRI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

Unadjusted analysis revealed significantly higher odds of in-hospital mortality, AKI, HF, stroke, CS, SCA, MI, temporary MCS use, and MACCE in COVID-19 patients with myocarditis compared to those without. Unadjusted estimates and outcome proportions are detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Bar graphs showing comparison of unmatched (left) and propensity-matched outcomes (right) in the myocarditis and nonmyocarditis groups.

Propensity score matching, adjusting for baseline demographics and comorbidities, yielded a matched sample of 630 patients per group (Supplementary Figure 2). The propensity-matched analysis largely corroborated the crude analysis findings. Adjusted outcomes for in-hospital mortality, MI, CS, HF, MCS use, MACCE, and AKI remained significantly elevated in patients with COVID-19 myocarditis. However, no significant difference was observed in SCA and stroke rates between the two groups (Figure 1).

Similarly, multivariate regression analysis showed that COVID-19 patients with myocarditis had significantly higher adjusted odds of in-hospital mortality (OR 1.59, 95% CI 1.27-1.9), CS (OR 10.2, 95% CI 7.9-13), SCA (OR 1.43, 95% CI 1.04-1.97), MCS use (OR 2.81, 95% CI 1.6-4.9), HF (OR 2.77, 95% CI 2.3-3.4), MACCE (OR 3.54, 95% CI 2.8-4.4), and AKI (OR 1.29, 95% CI 1.27-1.9) compared to those without myocarditis (Figure 2, Supplementary Table 6). Furthermore, myocarditis in COVID-19 hospitalization was associated with longer LOS (12.2 ± 13 days vs. 8 ± 9.5 days) and higher adjusted total charges ($223,992 ± $335,201 vs. $101,398 ± $194,987) (Supplementary Table 7).

Figure 3.

Graphical presentation of outcomes among patients with COVID-19 with and without myocarditis, respectively.

Figure 2.

Forest plot illustrating uOR (left) and aOR (right) for outcomes in patients with COVID-19–related myocarditis, using univariate and multivariate analysis. aOR = adjusted OR; uOR = unadjusted OR.

Overall, coronary angiography was performed in 230 patients (6.45%) with COVID-19 and myocarditis, and PCI in 15 (0.42%). Invasive coronary angiography use was significantly higher in myocarditis patients complicated by CS (13.9% vs. 5.3%, p<0.001).

Discussion

This study, utilizing the extensive NIS database, provides significant insights into the impact of myocarditis on COVID-19 hospitalizations. Key findings include: (1) a higher prevalence of COVID-19-associated myocarditis in men and individuals with pre-existing cardiac conditions such as MI, coronary artery bypass graft, PCI, and cardiac arrhythmias; (2) a lower risk of myocarditis in Caucasian populations compared to other racial groups; and (3) significantly worse in-hospital clinical outcomes, including mortality, CS, AKI, and MACCE, in COVID-19 patients with myocarditis.

The increased prevalence in men aligns with general myocarditis epidemiology, reporting male-to-female ratios from 1.5:1 to 1.7:1.10 , 11 Men often exhibit more pronounced neurohumoral activation and lower levels of natriuretic peptides, potentially contributing to adverse myocarditis outcomes.12 , 13 The study also noted a higher incidence in Black, Asian, and minority ethnic groups, potentially linked to higher rates of comorbidities like hypertension, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, known risk factors for severe COVID-19.1

The COVID-19 myocarditis group presented with a higher prevalence of complicated diabetes, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and liver disease – conditions independently associated with severe COVID-19 and poorer outcomes. Studies have shown increased in-hospital mortality in diabetic patients with COVID-19[14](#bib0014], and a meta-analysis highlighted CKD as a risk factor for severe COVID-19.15 Mortality rates escalate with worsening CKD severity.16 Similarly, cirrhosis in patients with chronic liver disease significantly increased 30-day mortality risk in COVID-19 cases.17 These comorbidities likely contributed to more severe COVID-19 in these patients, predisposing them to adverse outcomes, including myocarditis.

Consistently, COVID-19 myocarditis patients demonstrated worse clinical outcomes across all measured parameters, including in-hospital mortality, AKI, HF, CS, MACCE, and MCS needs. These findings remained significant after adjusting for confounders and effect modifiers in multivariate regression and propensity matching. Existing literature on COVID-19 myocarditis incidence and outcomes is limited. A retrospective cohort study of 718,365 COVID-19 patients found a 3.9% 6-month all-cause mortality (OR 1.36, 95% CI 1.21-1.53) in COVID-19 myocarditis patients, along with higher rehospitalization (OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.80-2.01) and acute MI (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.17-1.61) rates.18 A systematic review of 51 COVID-19 myocarditis patients reported a mean LOS of 14.9 days and a 14% pooled mortality rate.19 Another systematic review of 215 patients found a 31.8% in-hospital mortality and 14% CS rate, similar to our study’s findings.20

Interpreting large epidemiologic studies like ours requires careful consideration. Concerns exist about potential misdiagnosis of myocarditis in patients with elevated cardiac biomarkers. However, only 15% of our myocarditis cohort also had an MI diagnosis (including type 2 MI). The younger age and male predominance further support the myocarditis diagnoses in our sample. The extremely low percutaneous revascularization rate (0.3% overall) suggests routine ischemic evaluation may not be necessary in COVID-19 myocarditis. Even in CS patients, coronary intervention was deemed necessary in only 1%. While COVID-19-related myocarditis patients are demonstrably sicker, comprehensive management may be effectively delivered even in hospitals without PCI capabilities.

This study has limitations, primarily inherent to the cross-sectional nature of NIS data. Myocarditis diagnosis relied on ICD-10-CM codes, lacking biopsy, cardiac MRI, cardiac enzyme levels, or echocardiographic data, potentially introducing selection bias. To mitigate this, we specifically selected viral myocarditis related to COVID-19 using appropriate ICD-10-CM codes and employed multivariate regression and propensity score matching to control for potential confounders and effect modifiers. Vaccinated patients were not excluded, so vaccine-induced myocarditis cannot be entirely ruled out; however, vaccination was in early stages during the study period (2020), limiting its potential impact. Outpatient myocarditis cases are not included, potentially underrepresenting the overall risk. Longitudinal follow-up data is unavailable in NIS. As with all retrospective studies, potential selection and observational biases remain. While multivariate regression adjusted for confounding, unmeasured confounders may still influence results.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that COVID-19 patients with myocarditis experience significantly worse clinical outcomes, including higher in-hospital mortality and major adverse cardiovascular events. This risk is elevated in men, non-White individuals, and those with pre-existing cardiac comorbidities. Randomized controlled trials are needed to identify high-risk populations and to tailor preventative and treatment strategies to mitigate the public health impact of COVID-19-related cardiovascular complications.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Drs. Sattar and Sandhyavenu contributed equally to this work as primary authors.

Funding: none.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2023.01.004.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

mmc1.docx (836.5KB, docx)

References

[References]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

mmc1.docx (836.5KB, docx)