Introduction

The landscape of health care in the United States is vast and complex, with trillions of dollars spent annually. Within this intricate system, Medicare, the federal health insurance program for individuals 65 and older and certain younger people with disabilities, plays a crucial role. However, the sheer scale of Medicare also makes it vulnerable to fraud, with upcoding representing a significant area of concern. Upcoding, a practice where healthcare providers submit billing codes for more severe or extensive services than actually provided, inflates costs and undermines the integrity of the healthcare system. In 2015 alone, it was estimated that improper payments, a portion of which is attributed to fraudulent activities like upcoding, cost Medicare as much as $60 billion.

Understanding Medicare fraud, particularly upcoding, is crucial for several reasons. First, it directly impacts the financial sustainability of Medicare, potentially jeopardizing access to care for beneficiaries. Second, it distorts healthcare data, making it difficult to accurately assess healthcare needs and outcomes. Finally, it erodes public trust in the healthcare system and the professionals who are meant to uphold ethical standards. This article delves into the issue of upcoding in health care, exploring its definition, methods, impact, and the measures being taken to combat this form of fraud.

Medicare, as a cornerstone of the US healthcare system, is divided into several parts, each covering different aspects of medical care. Part A primarily covers inpatient hospital stays, skilled nursing facility care, hospice, and some home health services. Part B covers outpatient care, doctor visits, preventive services, and medical equipment. Part C, known as Medicare Advantage, allows private health insurance companies to provide Medicare benefits. Part D assists with prescription drug costs. The complexity of these parts and the numerous services covered create opportunities for fraudulent billing practices, including upcoding.

Upcoding takes various forms, all centered on misrepresenting the services provided to gain higher reimbursements. This can involve billing for unnecessary procedures, falsifying diagnoses to justify more expensive treatments, participating in illegal kickbacks, or, specifically, using codes for more severe conditions than actually diagnosed – the core definition of upcoding. The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes are the standardized language used to report medical procedures and services for billing purposes. Evaluation and Management (E&M) codes, a subset of CPT codes, are frequently used for office visits and patient encounters. The misuse or manipulation of these codes is central to upcoding practices. Some have described aggressive coding practices as “gaming the system,” particularly when related to risk assessment scores like the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) risk scores.

The adoption of Electronic Medical Records (EMRs) was initially seen as a tool to improve efficiency and accuracy in healthcare. However, the digital environment has also presented new avenues for upcoding if not properly monitored. Ideally, reimbursement should reflect the quality, quantity, and complexity of care provided, ensuring that upcoding and under-treatment are minimized. The Present on Admission (POA) indicator was introduced to differentiate between conditions present at the time of admission and those acquired during hospitalization, aiming to prevent hospitals from being paid more for hospital-acquired infections through upcoding.

Bundled payments, designed as a single payment for a full episode of care, aim to incentivize cost reduction and eliminate unnecessary services. Similarly, the Prospective Payment System (PPS) for inpatient hospital operating costs under Medicare Part A categorizes cases into Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs), each with a weight reflecting average resource use. Despite these systems, upcoding remains a challenge. The fee-for-service model, where clinicians are often paid based on Relative Value Units (RVUs), can inadvertently incentivize upcoding as clinicians may feel pressure to offset potential pay reductions by more aggressive coding.

Investigations have highlighted the prevalence of upcoding. For instance, a ProPublica analysis of Medicare billing data revealed that a significant number of providers consistently billed for the highest level of routine office visits, suggesting potential upcoding. The 99215 code, intended for complex and time-consuming visits, was used in all office visit billings by over 1,250 providers, raising red flags about billing practices.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) established the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program (HCFAC) to combat fraud. This program coordinates federal, state, and local law enforcement efforts to address healthcare fraud and abuse, including upcoding.

This article aims to explore the breadth and depth of upcoding in health care. By examining various studies and reports, it seeks to illuminate the impact of this fraudulent practice on the Medicare system and the broader healthcare landscape. The central question driving this exploration is: What is the magnitude of upcoding in inpatient and outpatient claims, and what are its ramifications for Medicare reimbursements and the integrity of health care?

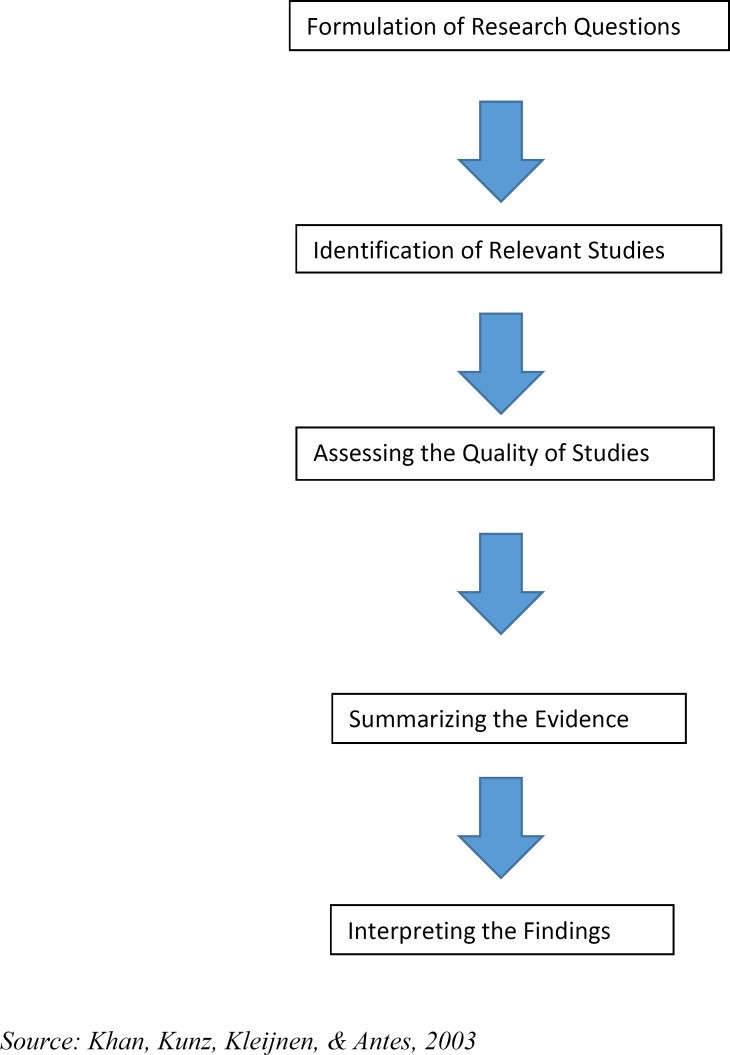

Figure 1: Research Framework. This image illustrates a typical research framework, often used in studies analyzing healthcare data and fraud detection methods.

Understanding the Methodology Behind Upcoding Research

Investigating the complex issue of upcoding in health care requires rigorous research methodologies. A common and effective approach is the literature review, which systematically examines existing academic sources to synthesize current knowledge and identify trends. This method is particularly useful in understanding the scope and impact of upcoding on Medicare and Medicaid.

One key hypothesis often explored in upcoding research is that fraudulent activity is on the rise, specifically through upcoding in ambulatory, inpatient, and outpatient charges billed to Medicare and Medicaid. To test this hypothesis, researchers often employ a structured literature review process. This process typically involves several stages, such as:

-

Developing a Search Strategy and Data Collection: This initial stage involves identifying relevant keywords and search terms related to upcoding, Medicare fraud, and related billing practices. Researchers then utilize these terms to search academic databases and other credible sources for relevant studies and reports.

-

Literature Analysis: Once a body of literature is collected, the next step is to analyze each source for its relevance to the research question. This involves critically evaluating the methodologies, findings, and conclusions of each study to determine its contribution to understanding upcoding.

-

Literature Categorization: To organize the findings from the literature review, researchers categorize the studies based on specific themes or areas of focus. This might include categorizing studies by the type of upcoding (e.g., DRG upcoding, emergency department upcoding), the healthcare setting (inpatient vs. outpatient), or the type of fraudulent activity investigated.

A widely adopted framework for conducting literature reviews is the five-step approach proposed by Khan et al. This approach provides a structured and comprehensive method for conducting systematic reviews, ensuring rigor and transparency in the research process. These five steps are:

-

Formulation of the Research Question: Clearly defining the research problem and the specific questions the review aims to answer. In the context of upcoding, this would involve specifying the focus on Medicare and Medicaid fraud related to upcoding.

-

Identification of Relevant Studies: Conducting a thorough search of relevant literature using predefined keywords and search strategies across multiple databases and sources.

-

Assessing the Quality of Studies: Evaluating the methodological rigor and validity of the identified studies to ensure that only high-quality and reliable evidence is included in the review. This step is crucial for maintaining the credibility of the literature review.

-

Data Extraction: Systematically extracting relevant data and findings from the selected studies. This may involve using standardized data extraction forms to ensure consistency and completeness.

-

Data Synthesis and Interpretation: Synthesizing the extracted data to identify patterns, themes, and key findings across the literature. This final step involves interpreting the synthesized evidence to draw conclusions and answer the research question.

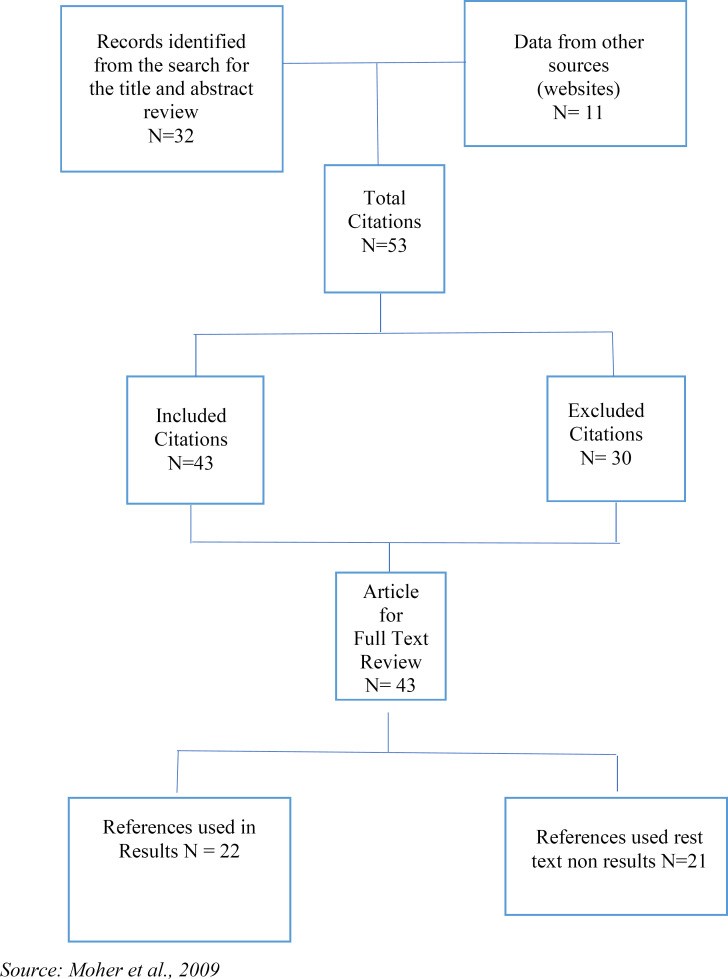

Figure 2: Overview of Literature Evaluation. This flowchart likely represents a PRISMA diagram or similar, outlining the process of literature search, screening, and selection for a systematic review or meta-analysis.

Step-by-Step Literature Identification and Collection

To effectively investigate upcoding through a literature review, a detailed search strategy is essential. This involves selecting relevant keywords and utilizing appropriate databases to gather academic peer-reviewed literature. Commonly used keywords in upcoding research include: “Medicare,” “Medicaid,” “Inpatients,” “Outpatients,” “Charges,” “Upcoding,” “Fraud,” “CPT,” “ICD-10-CM,” “ICD-10-PCS,” “Billing,” and “DRG.” These keywords are crucial for identifying studies specifically focused on healthcare fraud and upcoding within the Medicare and Medicaid systems.

Electronic databases such as JAMIA, Elibrary, PubMed, Medline, and Google Scholar are valuable resources for accessing academic literature. Following a systematic approach, such as the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, helps ensure a comprehensive and transparent search process. A typical search process might identify a large number of citations initially. However, many of these may be excluded if they do not meet pre-defined inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria are crucial for focusing the literature review on the most relevant studies. For research on Medicare fraud and upcoding, inclusion criteria might specify that articles must:

- Describe access to Medicare or Medicaid fraud.

- Specifically address upcoding charges.

- Be published within a certain timeframe to ensure the data is current and relevant (e.g., sources from 2008-2021).

- Be written in English to ensure accessibility for the research team.

- Originate from the United States to focus on the US healthcare system and regulations.

In addition to database searches, researchers may also include articles from other sources, such as reputable journals like The New England Journal of Medicine and The International Journal of Health Policy and Management, to capture a broader range of perspectives and insights. After applying inclusion criteria and conducting full-text reviews, a final set of citations are selected for data abstraction and analysis, forming the basis of the literature review’s findings.

Literature Analysis: Focusing on Key Areas of Upcoding

The analysis of the collected literature is a critical step in understanding the complexities of Medicare and Medicaid upcoding. This analysis focuses on key areas to provide a comprehensive picture of the issue. Given the significant financial impact of upcoding on hospitals through fraudulent inpatient and outpatient charges, the literature review often prioritizes sources that address these specific areas.

Key areas of focus for literature analysis in upcoding research include:

-

Medicare and Medicaid Upcoding and Fraud: This is the central theme, encompassing studies that broadly examine the nature, prevalence, and financial impact of upcoding within the Medicare and Medicaid systems.

-

Inpatient and Outpatient Charges: Analyzing literature that specifically investigates upcoding in both inpatient (hospital stays) and outpatient (clinic visits, procedures) settings is crucial, as upcoding practices and vulnerabilities may differ across these settings.

-

Billing, CPTs, and DRGs: A deep dive into the literature concerning billing codes (CPTs), diagnosis-related groups (DRGs), and their manipulation in upcoding schemes is essential. This includes understanding how specific codes are misused to inflate charges and generate fraudulent reimbursements.

To ensure the analysis is based on the most current and relevant information, researchers often limit their review to sources published within a specific timeframe, such as 2008-2021. This timeframe helps capture recent trends and developments in upcoding practices and detection methods. Furthermore, the analysis typically includes primary data (original research studies) and secondary data (literature reviews, reports, and analyses) from articles, research studies, and government reports originating from the United States, ensuring relevance to the US healthcare context.

To maintain rigor and validity in the literature review process, multiple researchers may be involved in the literature search and analysis. For example, one team of researchers might conduct the initial literature search, while another researcher acts as a second reader to validate the references and ensure they meet the pre-defined inclusion criteria. This double-checking process helps minimize bias and enhances the reliability of the literature review’s findings.

Literature Categorization: Structuring the Findings

Organizing the findings from a literature review into meaningful categories is essential for presenting a clear and structured understanding of the research topic. In the context of upcoding, categorization helps to highlight different facets of the issue and identify specific areas of concern. Common subheadings used to categorize literature on upcoding include:

-

Present on Admission Upcoding/Hospital Acquired Infections with Upcoding in Hospitals: This category focuses on studies examining upcoding related to conditions present at the time of hospital admission (POA) versus hospital-acquired infections (HAIs). It explores how providers may upcode diagnoses to circumvent penalties associated with HAIs and maintain reimbursements.

-

Diagnosis Related Group Upcoding in Hospitals: This category delves into research on upcoding within the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) system. DRGs are used to classify inpatient hospital stays for payment purposes, and studies in this category investigate how hospitals may manipulate DRG codes to increase reimbursements.

-

Upcoding with Surgeries and Anesthesia: This category focuses on upcoding practices associated with surgical procedures and anesthesia services. It may include studies examining the upcoding of anesthesia risk levels or the unbundling of services to maximize billing.

-

Emergency Department Upcoding: This category specifically addresses upcoding in the emergency department setting. Emergency departments are often vulnerable to upcoding due to the complexity of coding and the high volume of patients. Studies in this category may examine the upcoding of E&M codes for emergency visits.

-

Insurance Upcoding in Clinics and Hospitals: This broader category encompasses upcoding practices across both clinic and hospital settings, focusing on how insurance claims are manipulated to obtain higher reimbursements. This may include general upcoding of diagnoses or services in various clinical contexts.

By categorizing the literature in this way, researchers can systematically present the evidence and highlight the different dimensions of upcoding in health care. This structured approach makes the findings more accessible and facilitates a deeper understanding of the multifaceted nature of this fraudulent practice.

Key Findings: The Results of Upcoding Research

Research into upcoding in health care has revealed significant findings across various settings, highlighting the pervasive nature and financial impact of this fraudulent practice. Examining these results across different categories provides a comprehensive understanding of how upcoding manifests and affects the Medicare system.

Present on Admission/Hospital-Acquired Conditions Upcoding in Hospitals

One critical area of focus is upcoding related to Present on Admission (POA) indicators and Hospital-Acquired Conditions (HACs). Medicare legislation aims to improve patient care quality by reducing payments for HACs. However, studies indicate that this policy may be undermined by providers upcoding diagnoses to maintain higher reimbursements.

Research estimates that a substantial portion of claims, such as 10,000 out of 60,000, were improperly reimbursed for POA infections. Furthermore, it’s been reported that a significant percentage of claims, around 18.5%, involved upcoded hospital-acquired infections, costing Medicare an estimated $200 million. This suggests that despite policies aimed at reducing payments for HACs, upcoding is used to circumvent these measures and inflate costs. When reimbursement decreases due to DRG regulations related to POA infections, hospitals may be incentivized to upcode to offset these losses.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented the POA indicator to track conditions present at admission. Table 1 outlines the POA indicators and their payment implications.

Table 1. Present on Admissions for Fiscal Year 2018

| Indicator | Description | Payment |

|---|---|---|

| Yes (Y) | The diagnosis was present at the time of inpatient admission. | Payment is made for the condition when HAC is present. |

| No (N) | The diagnosis was not present at the time of inpatient admission. | No payment is made for the condition when HAC is present. |

| Unknown (U) | Documentation was insufficient to determine if the condition was present at the time of inpatient admission. | No payment was made for the condition when a HAC was present. |

| Undetermined (W) | Clinically undetermined. The provider was unable to clinically determine whether the condition was present at the time of inpatient admission. | Payment is made for the condition when HAC is present. |

Table 1: Present on Admissions for Fiscal Year 2018. This table details the CMS Present on Admission (POA) indicators used for billing and reimbursement, highlighting the payment implications based on whether a condition was present at the time of admission.

In 2012, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) estimated that a notable percentage of Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized experienced adverse events, and a portion of POA indicators were incorrectly reported by hospital coders. This incorrect reporting, even if seemingly small at 3% of claims, can have a significant financial impact when scaled across the vast number of Medicare claims. Hospitals that upcoded diagnosis codes with established complications received substantially higher payments, averaging around $6,398 per claim. This financial incentive further encourages upcoding practices related to POA and HACs.

Diagnosis-Related Group Upcoding in Hospitals

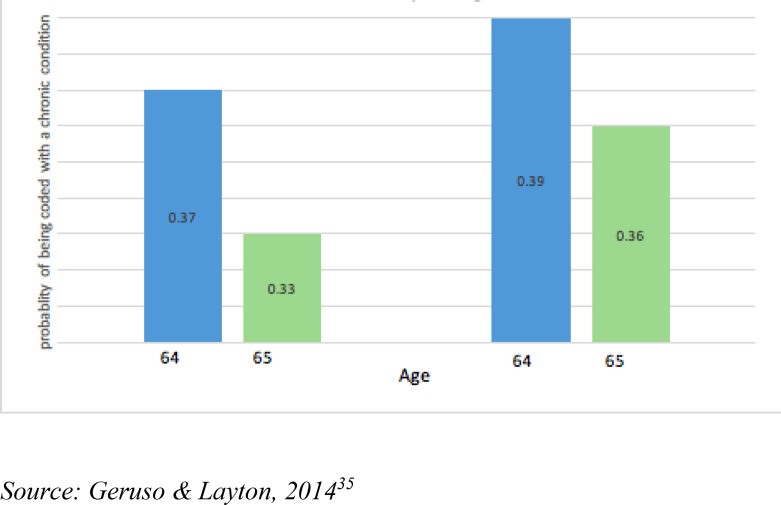

Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) upcoding is another significant area of concern. Research suggests that hospitals may strategically adjust admission types and treatment plans to maximize reimbursements within the DRG system. Figure 3 illustrates the probability of upcoding chronic conditions in Medicare, comparing fee-for-service plans with Medicare Advantage plans.

Figure 3: Medicare Upcoding with Chronic Conditions. This graph likely depicts a comparison of upcoding rates for chronic conditions between different types of Medicare plans, such as fee-for-service versus Medicare Advantage.

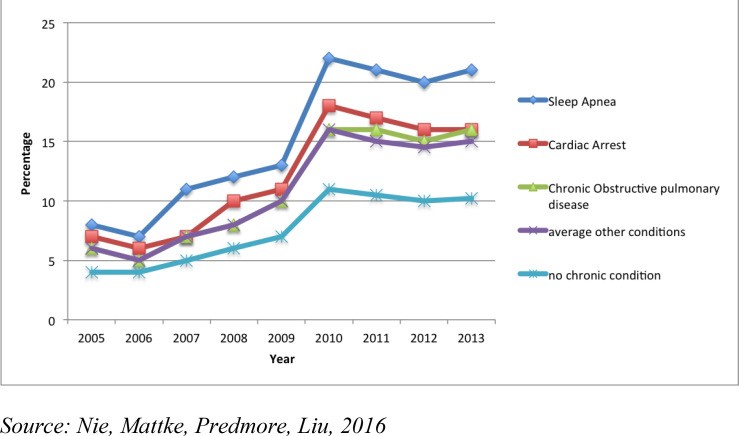

A study reviewing upcoding for high anesthesia risks and sleep apnea from 2005 to 2013 found a concerning trend. Upcoding patients as high-risk for anesthesia leads to increased claim payments. The study revealed a significant increase in reported ASA risk scores over this period, suggesting potential upcoding. Similarly, the proportion of patients coded with sleep apnea also increased substantially during the same timeframe. This indicates that conditions like high anesthesia risk and sleep apnea may be targeted for upcoding to boost revenue. Figure 4 further illustrates the trends of possible upcoding for high-risk anesthesia conditions.

Figure 4: Trends of Possible Upcoding for High-Risk Anesthesia Risk Conditions from 2005 to 2013. This line graph likely demonstrates the increasing trends in reported high-risk anesthesia conditions over time, potentially indicating upcoding.

Legal cases and investigations further underscore the issue of DRG upcoding. For example, Duke University settled a lawsuit for $1 million related to unbundled cardiac and anesthesia services. Another case in Florida involved a cardiologist performing unnecessary tests, knowing Medicare would provide higher reimbursement, highlighting a direct intent to defraud the system. This cardiologist received significantly higher Medicare reimbursements compared to peers, raising suspicions of widespread upcoding practices.

Estimates suggest that DRG upcoding can be incredibly costly. One report indicated that upcoding may have cost Medicare billions of dollars in a single year, translating to a substantial per-enrollee cost. This massive financial impact underscores the urgency of addressing DRG upcoding effectively.

Emergency Department Upcoding

Emergency departments (EDs) are particularly vulnerable to upcoding. Data shows an increase in ED visits over time, but a decrease in Medicare patients discharged, suggesting potential shifts in billing practices. Reports indicate that a significant proportion of Medicare ED patients are younger than 65, and a smaller percentage are of traditional Medicare age.

One concerning finding is that some medical centers have been reported to bill a large majority of their Medicare ED patients at the two highest, most expensive treatment levels. Furthermore, the use of the highest-level codes for ED visits has doubled over a period of years, even though many cases were not life-threatening. This dramatic increase in high-level coding suggests potential systematic upcoding in ED settings, adding billions to taxpayer costs.

The use of high-intensity ED visit codes, specifically level five visits (CPT code 99285), has grown significantly over time. CPT 99285 is intended for complex cases requiring comprehensive history, examination, and medical decision-making. Its increased use, alongside a decrease in lower-intensity codes (CPT codes 99281 and 99282 for low-complexity visits), further supports the notion of upcoding in EDs. While the use of high-level codes has increased, the use of low-complexity codes has decreased, indicating a shift towards higher billing levels, potentially irrespective of the actual complexity of patient cases.

Investigations and admissions of fraudulent activity in ED billing highlight the severity of the problem. Columbia Hospital Corporation, for example, admitted to filing false claims to Medicare and other federal programs and paid billions in fines and penalties for criminal activity, including ED upcoding.

Insurance Upcoding in Clinics and Hospitals

Upcoding is not limited to hospitals and EDs; it also occurs in clinics and across various insurance settings. Large healthcare corporations have faced legal repercussions for fraudulent charges related to incorrect diagnosis codes assigned to Medicare and Medicaid to inflate reimbursements. This type of upcoding involves assigning more severe diagnoses than actually warranted by the patient’s condition. An example would be coding a patient with pneumonia when they only present with cough and fever and haven’t been tested for pneumonia.

Individual providers have also been penalized for upcoding. A psychiatrist, for instance, was fined and excluded from Medicare and Medicaid for billing for longer session times than actually provided. Another form of upcoding involves billing established patient office visits using new patient evaluation and management codes, as Medicare reimburses new patient visits at higher rates.

Fraudulent enrollment practices in managed care programs also contribute to the broader issue of healthcare fraud. One case involved a healthcare organization fraudulently skewing enrollment in their Medicaid HMO program by refusing to enroll pregnant women and individuals with pre-existing conditions. This type of fraud, while not directly upcoding, demonstrates the range of unethical and illegal practices within the healthcare system that aim to maximize profits at the expense of program integrity and patient access.

The overall financial impact of Medicare and Medicaid fraud, including upcoding, is staggering. Estimates place the range of fraud in the hundreds of billions of dollars annually, requiring billions in spending to combat it. This immense scale underscores the need for continued vigilance and robust fraud prevention and detection efforts.

Discussion: Implications of Upcoding in Health Care

The findings from various research studies and investigations consistently point to a significant problem: upcoding in health care is a pervasive issue that inflates Medicare costs and undermines the integrity of the healthcare system. This literature review confirms the hypothesis that fraudulent activity has increased through upcoding in ambulatory, inpatient, and outpatient charges billed to Medicare and Medicaid.

One key driver of upcoding appears to be the pressure on healthcare providers to maintain high reimbursement levels. When regulatory measures or DRG classifications threaten to reduce reimbursements, hospitals and physicians may resort to upcoding to compensate for potential financial losses. This suggests a systemic issue where the financial incentives within the healthcare system inadvertently encourage fraudulent billing practices. The pressure to meet reimbursement quotas and avoid penalties further exacerbates this problem, creating a cycle of upcoding.

Research highlights that certain diagnoses are considered more profitable, leading hospitals to strategically adjust admission and treatment plans to increase the prevalence of these diagnoses. This strategic manipulation of patient classifications to maximize revenue is a direct consequence of the financial incentives within the fee-for-service system. The fact that upcoders often retain a large share of their fraudulent charges, even after deflators are applied, further incentivizes this behavior.

The physician’s role in classifying patient status within the coding system is critical. Studies show instances of physicians upcoding patient status, such as classifying patients as high-risk for anesthesia, solely to obtain higher Medicare reimbursements. Similarly, emergency department visits are frequently upcoded by using higher-level CPT codes than justified by the patient’s condition. The more frequent use of high-level codes like CPT 99285 compared to low-complexity codes like CPT 99281 is a clear indicator of potential upcoding practices aimed at maximizing reimbursement.

The deliberate miscoding of patient visits as “new patients” when they are established patients is another tactic used to exploit higher reimbursement rates for new patient visits. This type of upcoding, while seemingly simple, contributes to significant financial losses for Medicare over time.

Upcoding is not a victimless crime. It places an unnecessary burden on social safety nets like Medicare and Medicaid, which are essential for millions of individuals’ healthcare needs. The billions of dollars lost to upcoding could be used to improve patient care, expand coverage, or reduce healthcare costs for beneficiaries. Furthermore, widespread fraud erodes public trust in the healthcare system and the professionals entrusted with patient care.

Limitations of Upcoding Research

It is important to acknowledge the limitations inherent in research on upcoding and healthcare fraud. Literature reviews, while valuable, are subject to limitations related to search strategies, keyword selection, database access, and the sources included. These factors can potentially impact the comprehensiveness and quality of the reviewed literature.

Research bias and publication bias are also potential limitations. Studies that find significant evidence of upcoding may be more likely to be published than studies that do not, potentially skewing the overall picture. Furthermore, the reliance on publicly available data and reports may limit the depth and scope of the analysis, as some data on fraud detection and prevention efforts may be confidential or proprietary.

Practical Implications for Combating Upcoding

The ongoing monitoring of Medicare, Medicaid, and healthcare facilities is crucial for gathering more data and understanding evolving upcoding practices. Continuous data collection and analysis are essential for identifying trends, patterns, and emerging areas of vulnerability to fraud.

Future research should focus on analyzing claims data in conjunction with provider documentation and coded data to more accurately determine the true extent of upcoding in inpatient and outpatient claims. This type of detailed analysis can help identify specific providers or facilities that exhibit suspicious billing patterns and warrant further investigation.

Conclusion: Addressing Upcoding for a Sustainable Health Care System

Upcoding Medicare claims to secure higher reimbursements is a significant and costly problem within the US healthcare system. This review has confirmed that upcoding is a prevalent practice that contributes to Medicare fraud and abuse. To combat this issue effectively, continuous training for healthcare providers on ethical billing practices and proper coding procedures is essential. Education and awareness are key to preventing unintentional upcoding due to misunderstanding or errors.

Furthermore, promoting and strengthening whistleblower programs is crucial for encouraging the reporting of suspected upcoding and other forms of healthcare fraud. Rewarding and protecting whistleblowers can provide valuable insights into fraudulent activities that might otherwise go undetected. By fostering a culture of ethical billing and encouraging vigilance, the healthcare system can move towards mitigating the financial and ethical costs of upcoding and ensuring a more sustainable and trustworthy system for all.

Author Biographies

Alberto Coustasse, DrPH, MD, MBA, MPH, ([email protected]) is a professor of management and Administration Division at the Lewis College of Business | Brad D. Smith Schools of Business at Marshall University. He teaches at the Graduate MS Health Care and Health Informatics programs.

Whitney Layton, MS, Alumna Health care Administration, Lewis College of Business | Brad D. Smith Schools of Business at Marshall University.

Laykin Nelson, MS, Alumna Health Care Administration, Lewis College of Business | Brad D. Smith Schools of Business at Marshall University.

Victoria Walker MS Alumna Health Care Administration, Lewis College of Business | Brad D. Smith Schools of Business at Marshall University.

Notes

1 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare fraud & abuse. 2022. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/ProviderCompliance/Fraud-Abuse.html.