Introduction

The landscape of primary care in the United States is facing significant challenges, primarily due to a growing shortage of primary care physicians and an increasing population of aging and chronically ill individuals. Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs), where approximately 80 million Americans reside, are disproportionately affected by this scarcity of healthcare providers. This maldistribution of the healthcare workforce in HPSAs contributes to poorer health outcomes, including increased disease severity and reduced quality of life. Patients in these underserved areas often experience higher rates of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, further complicated by socioeconomic barriers to care.

Nurse practitioners (NPs) are increasingly recognized as a crucial resource in addressing these primary care demands, particularly in HPSAs. As the fastest-growing segment of the primary care workforce, NPs are well-equipped to provide comprehensive and holistic care, emphasizing not only physical health but also the social and emotional well-being of their patients. Their training uniquely positions them to manage complex cases, deliver chronic disease services, and enhance care coordination, especially for vulnerable populations in shortage areas. This article delves into the structural capabilities of primary care practices that utilize NPs, particularly within HPSAs, and explores how these capabilities can be optimized to improve patient care and access.

The Rising Role of Nurse Practitioners in Underserved Areas

The escalating demand for primary care, coupled with physician shortages, necessitates innovative solutions to ensure equitable healthcare access. NPs are stepping up to meet this challenge, with approximately 89% prepared to deliver primary care services. Studies have demonstrated that NPs achieve patient outcomes comparable to physicians, encompassing disease management, symptom reduction, and effective utilization of acute care services.

Notably, NPs are particularly adept at caring for patients with multiple chronic conditions and complex social needs – a demographic often prevalent in HPSAs. Compared to physicians, NPs are more likely to manage patients with three or more chronic illnesses and are more inclined to provide essential chronic disease services, including patient education and counseling. In states with full scope-of-practice regulations, NPs are even more likely to practice in HPSAs, significantly increasing access to care in these underserved regions. For example, full scope-of-practice authority for NPs is linked to an approximate 30% increase in annual check-ups within HPSAs, demonstrating their direct impact on improving healthcare accessibility.

Structural Capabilities: Enhancing Primary Care Delivery in HPSAs

While the growing presence of NPs in primary care is evident, understanding the specific practice infrastructure and integrated features – termed “structural capabilities” – they utilize to enhance care delivery in HPSAs is crucial. These structural capabilities are vital as they can directly improve primary care access and quality. Examples include extended practice hours, chronic care reminders integrated into provider workflows, and robust care coordination systems.

Care coordination, in particular, plays a pivotal role. It involves integrating personnel and activities to manage patient care seamlessly across the entire healthcare spectrum. Effective care coordination has been linked to significant benefits, including reduced medical expenditures, fewer inpatient hospitalizations, decreased emergency department (ED) visits, and lower 30-day readmission rates. Other structural capabilities, such as chronic disease registries, are designed to support providers in managing patients with chronic illnesses by providing tracking systems, clinician reminders, and checklists. These registries have proven effective in improving patient outcomes and helping practices maintain high standards of chronic care.

Despite the demonstrated benefits of structural capabilities, it remains unclear whether HPSA practices employing NPs are effectively implementing these features to address the complex needs of their patient populations. This understanding is essential to optimize the NP workforce and improve primary care access in underserved areas.

Study on Primary Care Practice Capabilities in HPSAs

To address this knowledge gap, a study was conducted to assess primary care practice structural capabilities in practices employing NPs, specifically comparing practices in HPSAs and non-HPSAs. This research utilized a secondary analysis of cross-sectional data from surveys of primary care NPs collected between 2018 and 2019, combined with publicly available data on HPSA designations.

The study focused on data from Arizona and Washington, states with full scope-of-practice regulations for NPs, as these states are more likely to see NPs practicing in HPSAs. The researchers analyzed data from 366 NPs across 269 practices in these states. HPSA designation was determined using a scoring system based on population-to-provider ratio, poverty levels, travel time to care, and infant health index. Practices were categorized as either HPSA (score 1-25) or non-HPSA (score 0).

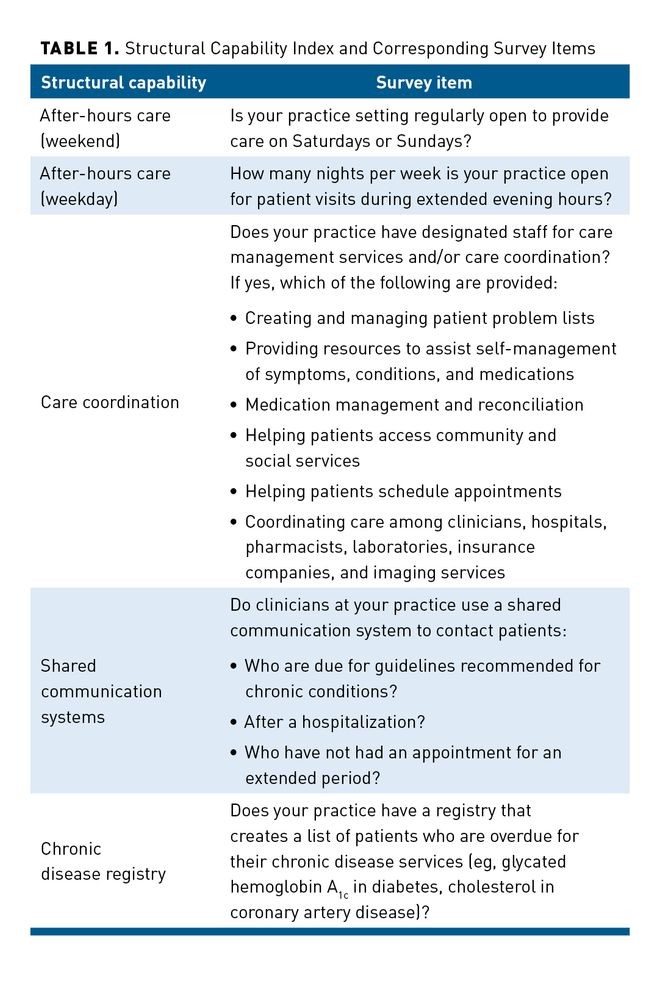

Structural capabilities were measured using the Structural Capability Index (SCI), a validated tool assessing primary care practice attributes linked to high-quality care. The study focused on four key SCI subscales:

- Shared systems for communication: Tools that improve communication between patients and providers.

- Care coordination: Integrated systems for managing patient care across different settings.

- Chronic disease registries: Systems for tracking and managing patients with chronic conditions.

- After-hours care: Availability of care outside of regular office hours.

Statistical analyses, including bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models, were used to compare NP and practice characteristics and to determine the likelihood of HPSA practices having specific structural capabilities compared to non-HPSA practices. The models controlled for NP demographics and practice characteristics to isolate the impact of HPSA designation.

Key Findings: Care Coordination in HPSA Practices

The study revealed that a significant majority (61%) of NPs in the sample practiced in HPSA-designated areas. While demographic characteristics of NPs were generally similar between HPSA and non-HPSA practices, some statistically significant differences emerged in educational degrees and practice certifications. NPs in HPSAs were more likely to have diverse specialties and less likely to hold only adult certifications.

Regarding structural capabilities, the most prevalent capability across all practices was chronic disease registries (65%), while after-hours care was less common. Crucially, the regression models demonstrated that NPs in HPSA practices were 68% more likely to deliver care coordination compared to NPs in non-HPSA practices. This significant difference remained even after adjusting for various NP and practice characteristics, with the adjusted odds ratio increasing to 1.77 (P < .05). Although not statistically significant, HPSA practices also showed a trend toward more frequent implementation of chronic disease registries.

These findings underscore that while various structural capabilities are important, care coordination stands out as a significantly more prevalent feature in HPSA practices utilizing NPs.

Discussion: Optimizing NP Roles Through Care Coordination

The study’s findings highlight the critical role of NPs in enhancing primary care, particularly in HPSAs, through the implementation of care coordination. The increased likelihood of care coordination in HPSA practices suggests a targeted response to the complex needs of patients in these areas, who often face multimorbidity and socioeconomic challenges. Care coordination, often delivered by NPs, is crucial for improving disease management and reducing ED utilization, especially for patients with complex needs.

While chronic disease registries also showed a positive trend in HPSA practices, the lack of statistical significance suggests potential areas for improvement. Disease registries offer a cost-effective approach to enhancing chronic care by improving adherence to guidelines and patient outcomes. Their potential for paper-based implementation could make them particularly valuable in resource-constrained HPSA settings.

The study’s focus on states with full scope-of-practice laws is important. It demonstrates the potential of NPs to optimize primary care in underserved areas when regulatory barriers are minimized. However, the study also acknowledges a limitation in the current HPSA designation criteria, which do not account for the presence of NPs and other non-physician providers. This oversight may affect the accuracy of HPSA evaluations and potentially underestimate the contributions of NPs in these areas. Future research should advocate for refining HPSA criteria to include NP availability, providing a more accurate assessment of primary care needs and resources in underserved communities.

Implications for Practice and Policy

The demonstrated benefits of care coordination, including improved quality of life and reduced healthcare costs, underscore the importance of its widespread adoption. However, the study reveals that only 43% of practices in the sample reported implementing care coordination. To bridge this gap, practices can focus on enhancing their infrastructure through dedicated personnel, electronic health records, and psychosocial resources. Furthermore, leveraging CMS chronic care management codes can incentivize practices by providing reimbursement for care coordination services for Medicare beneficiaries.

This study, conducted in full scope-of-practice states, suggests that the regulatory environment significantly impacts the ability of NPs to deliver structural capabilities like care coordination. Further research is needed to explore how varying scope-of-practice regulations across states influence the implementation of these capabilities and ultimately affect primary care access in HPSAs. Understanding these regulatory impacts is crucial for developing actionable policy recommendations to optimize NP care delivery and improve healthcare equity in underserved communities.

Limitations

The study’s limitations include its focus on only two states, potentially limiting the generalizability of the findings. The use of self-reported survey data may introduce self-report bias, although validated tools and rigorous methodology were employed to mitigate this. The study also focused on the presence of structural capabilities rather than their quality or effectiveness. Future research could explore the qualitative aspects of structural capability implementation and the impact of team-based care models involving NPs. Finally, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships.

Conclusion: Optimizing Primary Care with Nurse Practitioners in HPSAs

This study provides valuable insights into the structural capabilities of primary care practices employing NPs in HPSAs. The significant finding that HPSA practices are more likely to implement care coordination underscores the crucial role of NPs in addressing healthcare disparities in underserved areas. Expanding care coordination, alongside further exploration and implementation of other structural capabilities, holds significant potential for improving care for complex and chronically ill patients in HPSAs. Future research should focus on strategies to optimize the NP workforce and the implementation of structural capabilities to effectively meet the growing primary care demands in underserved communities, ultimately improving patient outcomes and access to quality healthcare.

References

- Duchovny N, Trachtman S, Werble E. Projecting demand for the services of primary care doctors. Congressional Budget Office. May 2017. Accessed February 5, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/workingpaper/52748-workingpaper.pdf

- Raghupathi W, Raghupathi V. An empirical study of chronic diseases in the United States: a visual analytics approach to public health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(3):431. doi:10.3390/ijerph15030431

- HPSA Find. Health Resources and Services Administration. Accessed January 5, 2021. https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/shortage-area/hpsa-find

- Allen NB, Diez-Roux A, Liu K, Bertoni AG, Szklo M, Daviglus M. Association of health professional shortage areas and cardiovascular risk factor prevalence, awareness, and control in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2011;4(5):565-572. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.960922

- Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of primary care physician supply with population mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(4):506-514. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624

- Streeter RA, Snyder JE, Kepley H, Stahl AL, Li T, Washko MM. The geographic alignment of primary care health professional shortage areas with markers for social determinants of health. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231443. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231443

- Auerbach DI, Staiger DO, Buerhaus PI. Growing ranks of advanced practice clinicians — implications for the physician workforce. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(25):2358-2360. doi:10.1056/nejmp1801869

- Nurse practitioners in primary care. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. Accessed January 6, 2021. https://www.aanp.org/advocacy/advocacy-resource/position-statements/nurse-practitioners-in-primary-care

- Buerhaus P, Perloff J, Clarke S, O’Reilly-Jacob M, Zolotusky G, DesRoches CM. Quality of primary care provided to Medicare beneficiaries by nurse practitioners and physicians. Med Care. 2018;56(6):484-490. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000908

- Kuo YF, Chen NW, Baillargeon J, Raji MA, Goodwin JS. Potentially preventable hospitalizations in Medicare patients with diabetes: a comparison of primary care provided by nurse practitioners versus physicians. Med Care. 2015;53(9):776-783. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000406

- Kurtzman ET, Barnow BS. A comparison of nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and primary care physicians’ patterns of practice and quality of care in health centers. Med Care. 2017;55(6):615-622. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000689

- Yang Y, Long Q, Jackson SL, et al. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and physicians are comparable in managing the first five years of diabetes. Am J Med. 2018;131(3):276-283.e2. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.08.026

- Grant J, Lines L, Darbyshire P, Parry Y. How do nurse practitioners work in primary health care settings? a scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2017;75:51-57. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.06.011

- Fraze TK, Briggs ADM, Whitcomb EK, Peck KA, Meara E. Role of nurse practitioners in caring for patients with complex health needs. Med Care. 2020;58(10):853-860. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000001364

- Lin SX, Gebbie KM, Fullilove RE, Arons RR. Do nurse practitioners make a difference in provision of health counseling in hospital outpatient departments? J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2004;16(10):462-466. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7599.2004.tb00425.x

- Ritsema TS, Bingenheimer JB, Scholting P, Cawley JF. Differences in the delivery of health education to patients with chronic disease by provider type, 2005-2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2014;11:E33. doi:10.5888/pcd11.130175

- DePriest K, D’Aoust R, Samuel L, Commodore-Mensah Y, Hanson G, Slade EP. Nurse practitioners’ workforce outcomes under implementation of full practice authority. Nurs Outlook. 2020;68(4):459-467. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2020.05.008

- Xue Y, Kannan V, Greener E, et al. Full scope-of-practice regulation is associated with higher supply of nurse practitioners in rural and primary care health professional shortage counties. J Nurs Regul. 2018;8(4):5-13. doi:10.1016/S2155-8256(17)30176-X

- Traczynski J, Udalova V. Nurse practitioner independence, health care utilization, and health outcomes. J Health Econ. 2018;58:90-109. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2018.01.001

- Friedberg MW, Coltin KL, Safran DG, Dresser M, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC. Associations between structural capabilities of primary care practices and performance on selected quality measures. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(7):456-463. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00006

- Martsolf GR, Ashwood S, Friedberg MW, Rodriguez HP. Linking structural capabilities and workplace climate in community health centers. Inquiry. 2018;55:46958018794542. doi:10.1177/0046958018794542

- Berkowitz SA, Parashuram S, Rowan K, et al; Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP) Team. Association of a care coordination model with health care costs and utilization: the Johns Hopkins Community Health Partnership (J-CHiP). JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(7):e184273. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.4273

- Powers BW, Modarai F, Palakodeti S, et al. Impact of complex care management on spending and utilization for high-need, high-cost Medicaid patients. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(2):e57-e63. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.42402

- Burton RA, Zuckerman S, Haber SG, Keyes V. Patient-centered medical home activities associated with low Medicare spending and utilization. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18(6):503-510. doi:10.1370/afm.2589

- Peterson KA, Carlin C, Solberg LI, Jacobsen R, Kriel T, Eder M. Redesigning primary care to improve diabetes outcomes (the UNITED Study). Diabetes Care. 2020;43(3):549-555. doi:10.2337/dc19-1140

- DesRoches CM, Barrett KA, Harvey BE, et al. The results are only as good as the sample: assessing three national physician sampling frames. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(suppl 3):S595-S601. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3380-9

- Hoddinott SN, Bass MJ. The Dillman total design survey method. Can Fam Phys. 1986;32:2366-2368.

- Harrison JM, Germack HD, Poghosyan L, D’Aunno T, Martsolf G. Methodology for a six-state survey of primary care nurse practitioners. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69(4):609-616. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2021.01.010

- Din A, Wilson R. Crosswalking zip codes to census geographies: geoprocessing the U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development’s zip code crosswalk files. Cityscape. 2020;22(1):293-314. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26915499

- Friedberg MW, Safran DG, Coltin KL, Dresser M, Schneider EC. Readiness for the patient-centered medical home: structural capabilities of Massachusetts primary care practices. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(2):162-169. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0856-x

- Martsolf GR, Kandrack R, Baird M, Friedberg MW. Estimating associations between medical home adoption, utilization, and quality: a comparison of evaluation approaches. Med Care. 2018;56(1):25-30. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000842

- Liederman EM, Morefield CS. Web messaging: a new tool for patient-physician communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2003;10(3):260-270. doi:10.1197/jamia.M1259

- Sada YH, Street RL Jr, Singh H, Shada R, Naik AD. Primary care and communication in shared cancer care: a qualitative study. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(4):259-265.

- Hoque DME, Kumari V, Hoque M, Ruseckaite R, Romero L, Evans SM. Impact of clinical registries on quality of patient care and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0183667. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183667

- Jerant A, Bertakis KD, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Extended office hours and health care expenditures: a national study. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(5):388-395. doi:10.1370/afm.1382

- O’Malley AS. After-hours access to primary care practice linked with lower emergency department use and less unmet medical need. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):175-183. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0494

- Capp R, Misky GJ, Lindrooth RC, et al. Coordination program reduced acute care use and increased primary care visits among frequent emergency care users. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1705-1711. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0612

- Orzano AJ, Strickland PO, Tallia AF, et al. Improving outcomes for high-risk diabetics using information systems. J Am Board Fam Med. 2007;20(3):245-251. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2007.03.060185

- Liu JJ. Health professional shortage and health status and health care access. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(3):590-598. doi:10.1353/hpu.2007.0062

- Marek KD, Stetzer F, Ryan PA, et al. Nurse care coordination and technology effects on health status of frail older adults via enhanced self-management of medication: randomized clinical trial to test efficacy. Nurs Res. 2013;62(4):269-278. doi:10.1097/NNR.0b013e318298aa55

- Friedman A, Howard J, Shaw EK, Cohen DJ, Shahidi L, Ferrante JM. Facilitators and barriers to care coordination in patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) from coordinators’ perspectives. J Am Board Fam Med. 2016;29(1):90-101. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2016.01.150175

- Agarwal SD, Barnett ML, Souza J, Landon BE. Medicare’s care management codes might not support primary care as expected. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(5):828-837. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00329