Fracture care coding can often appear straightforward on the surface, but beneath this simplicity lies a complex web of nuances and potential pitfalls. Misconceptions and confusion surrounding fracture types and proper billing practices are surprisingly common, even amongst seasoned professionals. To help you navigate these challenges and ensure accurate coding and billing, we’re here to set the record straight and provide you with everything you need to know about fracture care – and how Fracture Care Coding Webinars can be your key to mastery.

Understanding the Fundamentals: What is a Fracture?

Let’s begin by dispelling a common myth: a fracture is not merely a “hairline break” or a specific kind of broken bone. In medical terminology, “fracture” and “broken bone” are interchangeable terms describing the same condition – a disruption in the continuity of a bone.

Decoding Fracture Types: A Comprehensive Overview

The world of fractures is diverse, encompassing a wide array of classifications based on the fracture pattern and bone displacement. Some common types you’ll encounter in coding include:

- Transverse Fractures: The fracture line is perpendicular to the long axis of the bone.

- Oblique Fractures: The fracture line runs at an angle across the bone shaft.

- Spiral Fractures: The fracture line spirals around the bone shaft, often due to a twisting injury.

- Angulated Fractures: The bone fragments are misaligned at an angle.

- Displaced Fractures: The bone fragments are separated and not in anatomical alignment.

- Angulated and Displaced Fractures: A combination of both angulation and displacement.

While these are broad categories, the specific types of fractures are incredibly numerous and detailed. For instance, consider these examples:

- Barton’s fracture: A fracture of the distal radius extending into the wrist joint.

- Fissure fracture: A crack on the bone surface that doesn’t completely penetrate the bone.

- Jefferson’s fracture: A fracture of the atlas vertebra (C1).

- Lead pipe fracture: A slight compression and bulging of the bone cortex on one side with a crack on the opposite side.

- Parry fracture/Monteggia’s fracture: A fracture of the ulna’s proximal shaft with dislocation of the radial head.

- Ping-pong fracture: A depressed skull fracture, mainly in children, resembling a ping-pong ball indentation.

- Pott’s fracture: A fracture of the distal fibula, often with injury to the tibial articulation, possibly including malleolus chipping or medial ligament rupture.

- Colles’ fracture: A fracture of the distal radius with dorsal displacement of the distal fragment. A volar displacement is termed a reverse Colles’ fracture.

This list is far from exhaustive. Accurate coding hinges on precise fracture identification. Therefore, having a medical dictionary or orthopedic coding resource readily available is invaluable when reviewing fracture documentation and encountering unfamiliar terminology. To deepen your understanding of these nuances and stay updated with the latest coding guidelines, fracture care coding webinars offer a focused and efficient learning avenue.

Fracture Fixation: Reduction and Treatment Modalities

The primary goal in fracture treatment is to facilitate optimal bone healing. Immobilization is key, often achieved through casting. In some cases, surgical intervention is necessary to properly align the fractured bone segments.

Before casting or surgical fixation, the bone must be restored to its correct anatomical position – a process known as “reduction.”

- Closed Reduction: This involves manipulating the fracture externally, without surgical incision.

- Open Reduction: This requires a surgical incision to access the fracture site for manipulation and alignment.

When coding fractures, it’s essential to identify the type of reduction performed (closed or open), the affected body part (arm, leg, finger, etc.), and sometimes the precise fracture location (e.g., femoral head vs. shaft).

Visualizing Fracture Reduction: X-Ray Examples

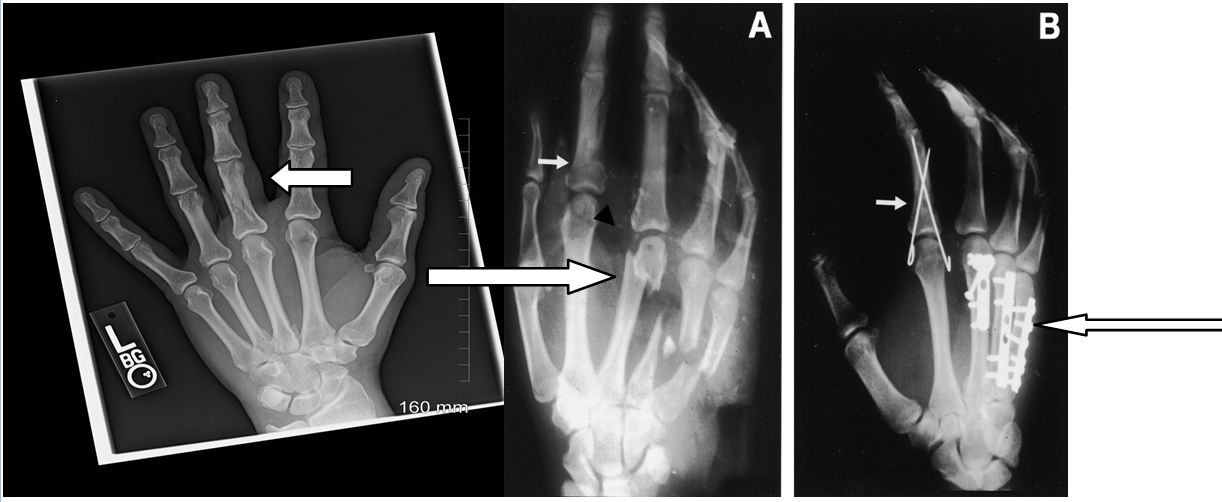

Consider the X-ray images below to illustrate different fracture types and reduction methods.

The left X-ray demonstrates a minimally displaced fracture of the proximal phalanx of the long finger. This could represent a closed treatment of a phalangeal fracture, coded as CPT® 26720 (closed treatment without manipulation) or 26725 (closed treatment with manipulation), depending on physician documentation.

Film A shows a displaced index finger fracture (short arrow) and multiple metacarpal fractures (long arrow). Film B illustrates a percutaneous pin fixation (short arrow, CPT® 26727) and internal fixation with plates and screws (long arrow, CPT® 26615). Other internal fixation methods include rods and spheres. Understanding these different fixation techniques is crucial for accurate coding. Fracture care coding webinars often provide detailed visual examples and case studies to enhance comprehension of these procedures.

Billing for Fracture Care: Navigating Global Fees and Alternative Methods

Two primary approaches exist for billing non-manipulative fracture care services, endorsed by both the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Medical Association (AMA). These are detailed in CPT® Assistant publications.

-

Fracture Global Fees:

The AAOS defines fracture global fees as potentially encompassing the hospital or office encounter in some payment settings. CMS may allow coding an E/M service with modifier -57 (Decision for surgery) within the global period if the visit was when the surgical decision was made. The initial cast or splint and all subsequent revisits (excluding physician-obtained radiographs) are included within a 90-day period from the initial fracture. Recasting or splinting is billed separately per encounter.

-

Alternative Method for Fracture Fees:

The AAOS defines this method for cases where fracture treatment doesn’t primarily involve a “procedure,” such as closed treatment without manipulation. Services are itemized as office encounters. Examples include undisplaced fifth metatarsal fractures, minimally displaced pelvic fractures, or vertebral compression fractures. Office, hospital, and ED encounters are coded appropriately, along with injections, supplies, casts, splints, or treatment necessities.

Payer policies vary. For office-based fracture care, payers may require modifier 25 (Significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician on the same day of the procedure or other service) with the E/M service. Practices must decide whether to bill fracture treatment globally or itemize based on the specific scenario and payer guidelines. Navigating these billing complexities can be challenging. Fracture care coding webinars frequently dedicate sessions to clarifying billing rules and payer-specific nuances.

Coding Example 1: Closed Reduction Without Manipulation vs. E/M

Reporting Closed Reduction w/o Manipulation:

- Cast/splint/strapping is included in the procedure code.

- X-rays and supplies can be reported separately.

Reporting an E/M Service:

- Cast/splint application, X-rays, and supplies are all separately reportable.

Closed reduction with manipulation includes a 90-day global package. The initial casting, splinting, and strapping, along with post-operative visits within this period, are bundled into the procedure code. X-rays, DME, and casting/splinting supplies are billed separately. During the global period, separate E/M services related to the fracture care are not billable. For example, if reporting procedure code 26725:

- Procedure: 26725

- Do not code separately for cast or splint application.

- Next visit (related to post-op): 99024 (Postoperative follow-up visit, included in surgical package)

- Cannot bill separately for related E/M services during the 90-day global period.

- Casting/Splinting Supplies: Report supply charges separately based on documentation.

To gain a deeper understanding of global periods and bundled services in fracture care coding, consider attending specialized webinars that delve into these complex billing scenarios.

Coding Example 2: Fractured Clavicle and Minimal Follow-Up

Consider a patient presenting with a non-displaced clavicle fracture who is given a sling and PRN follow-up instructions. Can fracture care be billed? Is this considered treatment if no scheduled return visit is planned?

Remember, fracture care codes (and surgical procedures) encompass preoperative, operative, and postoperative components.

Physician Reimbursement Breakdown (Approximate):

- 17% Preoperative

- 63% Operative

- 20% Postoperative

In this clavicle fracture example, if no follow-up is intended, the postoperative portion is essentially eliminated. Billing a fracture treatment code might be inappropriate. Similar to an ED physician treating a fracture without planned follow-up, an E/M service, rather than a fracture care code, would be the correct choice. Fracture care coding webinars often use real-world examples like these to clarify appropriate coding and billing strategies in various clinical scenarios.

Coding Example 3: Transfer of Postoperative Fracture Care

A patient injured in Utah undergoes surgery and returns home to New Jersey for follow-up care. How is reimbursement handled?

Ideally, the Utah surgeon should receive 17% (preoperative) + 63% (operative). If aware of the patient’s relocation, they should append modifier 54 (Surgical care only) to the fracture care code and inform the New Jersey orthopedist about the transfer of care. The New Jersey orthopedist, accepting postoperative care, would bill the same surgical code with modifier 55 (Postoperative care), receiving 20% (postoperative fee).

However, this ideal scenario is rare in practice. Surgeons are often hesitant to relinquish a portion of their surgical fee. In such situations, communication is key. The New Jersey orthopedist should contact the Utah surgeon to discuss fee splitting and potentially file a corrected claim if the initial claim has already been submitted. Without communication and documentation of transferred care, billing for postoperative care in New Jersey is not permissible. Webinars on fracture care coding often address inter-physician billing scenarios and the proper use of modifiers in shared care situations.

Equipping Yourself with the Right Tools and Knowledge

For coders specializing in orthopedics, AAPC’s Certified Orthopaedic Surgery Coder (COSC™) exam validates your expertise. Staying current with coding guidelines is paramount. Utilize up-to-date medical coding books and resources. AAPC Coder provides a fast and comprehensive code search engine for efficient claims processing.

Elevate Your Fracture Care Coding Skills with Webinars

In today’s rapidly evolving healthcare landscape, continuous learning is essential. Fracture care coding webinars offer a dynamic and accessible way to master the intricacies of fracture coding, stay abreast of coding updates, and refine your billing strategies. These webinars provide:

- Expert-led instruction: Learn from seasoned coding professionals with extensive experience in orthopedics.

- In-depth knowledge: Gain comprehensive insights into fracture types, treatment modalities, coding guidelines, and billing best practices.

- Real-world case studies: Analyze practical examples and complex scenarios to enhance your coding decision-making.

- Interactive Q&A sessions: Get your specific coding questions answered by webinar experts.

- Convenient online format: Learn at your own pace and schedule from anywhere with internet access.

Investing in fracture care coding webinars is an investment in your professional growth and coding accuracy. By participating in these focused educational sessions, you can confidently navigate the complexities of fracture care coding, optimize reimbursement, and minimize coding errors. Don’t let fracture coding challenges hold you back – empower yourself with the knowledge and skills you need to excel. Explore fracture care coding webinars today and take your expertise to the next level.

Author Bio:

Cynthia Everlith, BSHA, CPC, CMA, is practice administrator for Arizona Hand and Wrist Specialists, a division of OSNA, PLLC. She has more than 25 years of experience in orthopaedic coding and practice management, and 16 years with her current practice. She is actively involved in workers’ compensation legislation and has worked closely with the Industrial Commission of Arizona and the Arizona Medical Association in rules affecting physicians. She has presented nationally and locally. She is a past American Association of Orthopaedic Executives (AAOE) Board of Directors and past president of AAPC’s Grand Canyon Coders Phoenix chapter. She serves on the AAOE Communication Council and Technology Task Force, and is president of the Arizona AAOE Chapter.