Fracture care coding can present complexities for even seasoned medical coders. Understanding the nuances of fracture types, treatment methodologies, and the specific coding guidelines is crucial for accurate billing and reimbursement. This guide aims to clarify the essential aspects of fracture care coding, drawing from established guidelines and best practices relevant to 2020 and beyond.

Understanding Fractures: Beyond a Simple Break

The term “fracture” is often used interchangeably with “broken bone,” and this understanding is fundamentally correct. It’s not just about hairline cracks or specific types of breaks; any disruption in the continuity of a bone is classified as a fracture.

Classifying Fracture Types: A Spectrum of Breaks

Fractures are diverse, varying significantly in nature and severity. Accurate coding hinges on a precise understanding of these different fracture classifications. Some common types include:

- Transverse Fractures: These fractures occur when the break is in a straight horizontal line across the bone.

- Oblique Fractures: Characterized by a break that is diagonal or slanted across the bone.

- Spiral Fractures: These fractures result from a twisting force, causing the break to spiral around the bone shaft.

- Angulated Fractures: Involve a fracture where the broken bone fragments are at an angle to each other.

- Displaced Fractures: Occur when the bone fragments are separated and no longer in their normal alignment.

- Angulated and Displaced Fractures: A combination of both angulation and displacement, representing a more complex fracture.

To further illustrate the breadth of fracture classifications, consider these specific examples:

- Barton’s Fracture: A fracture affecting the distal radius and extending into the wrist joint. This was previously coded under ICD-9-CM 813.42 (Other closed fractures of distal end of radius (alone)).

- Fissure Fracture: A crack in the bone surface that doesn’t completely penetrate through the bone, often seen in long bones.

- Jefferson’s Fracture: A fracture of the atlas, the first cervical vertebra (C1), typically resulting from axial compression.

- Lead Pipe Fracture: A fracture where one side of the bone cortex is compressed and bulging, with a minor crack on the opposite side.

- Parry Fracture (Monteggia’s Fracture): Involves a fracture of the proximal ulna shaft coupled with a dislocation of the radial head. Previously coded as ICD-9-CM 813.03 (Closed Monteggia’s fracture).

- Ping-Pong Fracture: A depressed skull fracture, mainly seen in infants, that resembles an indentation in a ping-pong ball, and can often be manually elevated back into position.

- Pott’s Fracture: A fracture of the distal fibula, frequently accompanied by damage to the distal tibial articulation, potentially including a medial malleolus chip fracture or medial ligament rupture.

- Colles’ Fracture: A fracture of the distal radius where the broken fragment is displaced dorsally (backward). A volar (forward) displacement is termed a reverse Colles’ fracture. Previously coded as ICD-9-CM 813.41 (Closed Colles’ fracture).

This is just a glimpse into the extensive list of fracture types. When coding, a comprehensive medical dictionary or orthopedic coding resource is invaluable for deciphering unfamiliar terms and ensuring accurate code selection.

Figure 1: Visual representation of different fracture types including transverse, oblique, spiral, angulated, displaced, and angulated displaced fractures.

Fracture Treatment: Reduction and Fixation Explained

The primary goal of fracture treatment is to facilitate proper bone healing. Immobilization is often key, typically achieved through casting. In many cases, surgical intervention is necessary to correctly align the bone fragments.

Reduction: Restoring Alignment

Before casting or surgical fixation, the fractured bone must be returned to its anatomical position. This process is known as “reduction.”

- Closed Reduction: This involves manipulating the fracture externally, without making an incision.

- Open Reduction: Surgical exposure of the fracture site is required to manipulate and align the bone fragments.

Coding fracture care demands a clear understanding of the reduction type (open or closed), the affected body part (arm, leg, finger, foot, etc.), and sometimes the precise fracture location within the bone (e.g., femoral head vs. femoral shaft).

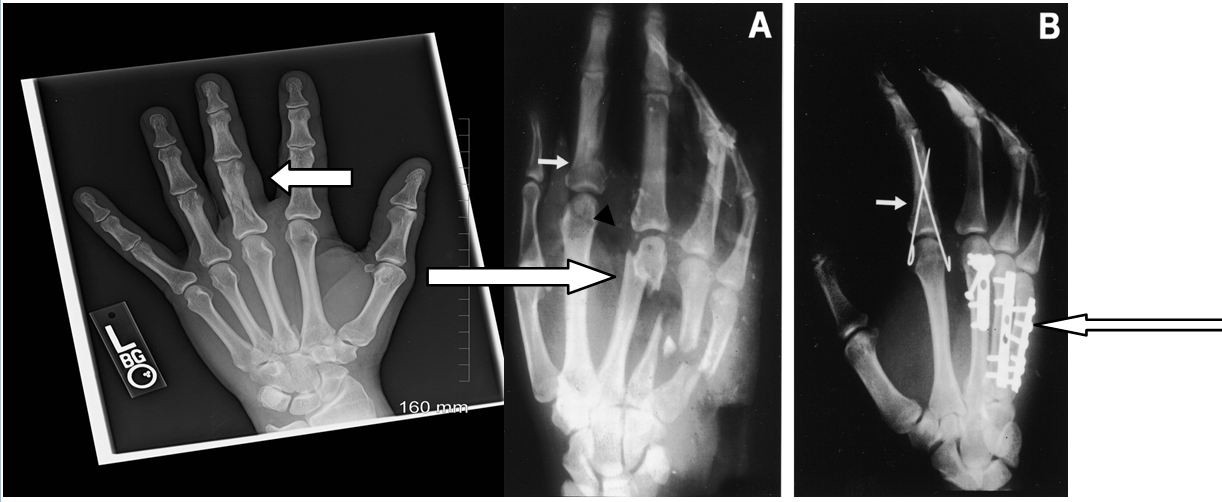

Figure 2 provides visual examples of different fracture types and reduction methods.

The X-ray on the left of Figure 2 illustrates a fracture of the proximal phalanx of the long finger (third finger). This fracture is minimally displaced. Depending on the physician’s documentation, coding could involve:

- 26720 (Closed treatment of phalangeal shaft fracture, proximal or middle phalanx, finger or thumb; without manipulation, each) for closed treatment without manipulation.

- 26725 (Closed treatment of phalangeal shaft fracture, proximal or middle phalanx, finger or thumb; with manipulation, with or without skin or skeletal traction, each) for closed treatment with manipulation.

On Film A of Figure 2, the short arrow indicates a displaced fracture of the index finger, while the long arrow points to multiple metacarpal fractures. On Film B, the short arrow highlights a percutaneous pin fixation (coded as 26727 – Percutaneous skeletal fixation of unstable phalangeal shaft fracture, proximal or middle phalanx, finger or thumb, with manipulation, each), and the long arrow shows an internal fixation using plates and screws (coded as 26615 – Open treatment of metacarpal fracture, single, includes internal fixation, when performed, each bone). Other internal fixation methods include rods and spheres.

Billing for Fracture Care: Navigating Global Fees and Alternative Methods

When coding for non-manipulative fracture care, two primary billing methodologies are commonly recognized and endorsed by organizations like the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Medical Association (AMA):

- Fracture Global Fees: This approach bundles various services under a single, comprehensive fee.

- Alternative Method for Fracture Fees: This method allows for itemizing individual services.

Fracture Global Fees: A Bundled Approach

According to the AAOS Guide to CPT® Coding for Orthopaedic Surgery, the fracture global fee method encompasses:

“Fracture global fees may include the hospital or office encounter in some payment areas. In others, CMS allows you to code an E/M service with a -57 modifier [*Decision for surgery*] within the global period if the visit was the one in which the decision to perform the procedure was made. The initial cast or splint is applied, and all revisits, excluding radiographs that are obtained by the physician, should be included within a 90-day period from the time of the initial fracture. All recastings and or splinting are on an ‘encounter’ basis and are separately billed.”

Under the global fee structure, an initial visit (where the decision for surgery is made – potentially billable with modifier -57), the fracture reduction procedure itself, application of the initial cast or splint, and routine follow-up visits within 90 days are typically included in the global fee. Radiographs taken by the physician, recasting, and splinting beyond the initial application are usually billed separately.

Alternative Method: Itemizing Services

The AAOS defines the alternative method as:

“Only when treatment of the fracture does not consist primarily of a ‘procedure’ (for example, closed treatment without manipulation), services may be itemized as if the problem were recognized as an office encounter. Examples include an undisplaced fracture of the fifth metatarsal; a fracture of the pelvis, undisplaced or minimally displaced; or a compression fracture of a vertebra. Office, hospital, and emergency department encounters are coded as appropriate, as are all injections, supplies, casts, splints or treatment program necessities.”

This alternative approach is applicable when the fracture treatment is primarily non-procedural, such as in cases of undisplaced or minimally displaced fractures. In these instances, services are itemized, allowing for separate billing of E/M services (office, hospital, ED visits), injections, supplies, casts, splints, and other necessary treatment components.

Payer-Specific Guidelines: It’s crucial to remember that payer policies vary. For office-based fracture care, payers may require modifier 25 (Significant, separately identifiable evaluation and management service by the same physician on the same day of the procedure or other service) to be appended to the E/M code when billing an E/M service on the same day as fracture care. Practices must determine the most appropriate billing method (global fee vs. itemized) based on the specific clinical scenario and payer requirements.

Coding Examples: Applying Fracture Care Coding Principles

Let’s examine practical coding scenarios to solidify understanding.

Coding Example 1: Closed Reduction without Manipulation vs. E/M Service

Scenario: A patient presents with a fracture treated via closed reduction without manipulation.

If reporting closed reduction without manipulation:

- The cast, splint, or strapping is considered part of the procedure code.

- X-rays and supplies can be billed separately.

If reporting an E/M service:

- Cast/splint application, X-rays, and supplies can all be billed separately, in addition to the E/M service.

When a closed reduction code is reported, it encompasses a 90-day global period. The initial casting, splinting, and strapping are bundled into the procedure code, along with routine postoperative visits within this period. Services excluded from the global package and billable separately include X-rays, DME, and casting/splinting supplies. Importantly, separate E/M services related to the fracture care during the 90-day global period are not typically billable. A follow-up visit within the global period, if necessary and related to the original procedure, can be indicated using code 99024 (Postoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package, to indicate that an evaluation and management service was performed during a postoperative period for a reason(s) related to the original procedure), but this is for informational purposes and not separately reimbursed.

Example Coding Scenario: For a closed reduction with manipulation (e.g., code 26725), do not separately code for cast or splint application. Subsequent related visits within the global period are not separately billable. Casting and splinting supplies, however, can be reported separately.

Coding Example 2: Fractured Clavicle and Initial Sling Application

Scenario: A patient with a non-displaced clavicle fracture is treated in the office with a sling and instructed to follow up as needed (PRN). Can fracture care coding be applied?

Consideration: Fracture care codes (and surgical procedure codes in general) inherently include preoperative, operative, and postoperative components in their valuation. Physician reimbursement is typically allocated as follows:

- 17% Preoperative

- 63% Operative

- 20% Postoperative

In this clavicle fracture example, if there is no planned follow-up care by the provider, the postoperative component is essentially eliminated. Billing a fracture treatment code in this scenario may be inappropriate. Similar to an ED physician treating a fracture without planned follow-up, reporting an appropriate E/M service might be more accurate than a fracture care code in such cases.

Coding Example 3: Transfer of Postoperative Fracture Care

Scenario: A patient undergoes fracture surgery in Utah but resides in New Jersey and seeks postoperative care closer to home. How is reimbursement handled?

Ideal Scenario: The Utah surgeon performing the surgery ideally should bill for the preoperative (17%) and operative (63%) portions using the fracture care code with modifier 54 (Surgical care only). They should also communicate the transfer of care to the New Jersey orthopedist, providing written documentation. The New Jersey orthopedist assuming postoperative care would then bill the same surgery code with modifier 55 (Postoperative care), receiving the 20% postoperative fee allocation.

Real-World Challenges: In practice, this ideal scenario is rarely fully realized. Surgeons are often reluctant to relinquish 20% of their surgical fee for postoperative care. Similarly, physicians may be hesitant to accept a 20% payment for managing another physician’s surgical case.

Practical Solutions: In such situations, communication is key. The New Jersey orthopedist should contact the Utah surgeon to discuss the situation. If the Utah surgeon agrees to split the fee and has already filed a claim, a corrected claim may be necessary. Without communication and documented transfer of care, billing for postoperative care by the accepting orthopedist may not be possible.

Essential Tools for Orthopaedic Coding Accuracy

For coders specializing in orthopaedic coding, professional certification like the Certified Orthopaedic Surgery Coder (COSC™) credential demonstrates expertise and value. Staying current with coding guidelines is paramount for compliance. Utilizing up-to-date medical coding books and comprehensive coding search engines like AAPC Coder are invaluable resources for efficient and accurate orthopaedic coding.

Author Bio: Cynthia Everlith, BSHA, CPC, CMA, is practice administrator for Arizona Hand and Wrist Specialists, a division of OSNA, PLLC. She has more than 25 years of experience in orthopaedic coding and practice management, and 16 years with her current practice. She is actively involved in workers’ compensation legislation and has worked closely with the Industrial Commission of Arizona and the Arizona Medical Association in rules affecting physicians. She has presented nationally and locally. She is a past American Association of Orthopaedic Executives (AAOE) Board of Directors and past president of AAPC’s Grand Canyon Coders Phoenix chapter. She serves on the AAOE Communication Council and Technology Task Force, and is president of the Arizona AAOE Chapter.