Fracture care coding can be complex, especially when navigating the nuances of different fracture types and billing procedures. Understanding the established guidelines is crucial for accurate coding and reimbursement. Let’s delve into the essential aspects of fracture care coding, focusing on the guidelines relevant to 2017, to clarify common misunderstandings and ensure proper claim submission.

Understanding Fractures: Beyond the Basics

Contrary to popular belief, the terms “fracture” and “broken bone” are interchangeable. A fracture isn’t just a minor crack; it represents any disruption in the continuity of a bone. Recognizing the different types of fractures is fundamental to appropriate coding and treatment.

Types of Fractures: A Detailed Look

Fractures are categorized based on their pattern and characteristics. Common types include:

- Transverse Fractures: These fractures occur straight across the bone shaft.

- Oblique Fractures: Oblique fractures have a slanted pattern across the bone.

- Spiral Fractures: These fractures spiral around the bone shaft, often resulting from twisting injuries.

- Angulated Fractures: In angulated fractures, the bone fragments are misaligned at an angle.

- Displaced Fractures: Displaced fractures involve bone fragments that are separated and not in anatomical alignment.

- Angulated and Displaced Fractures: These fractures combine both angulation and displacement of bone fragments.

Beyond these general categories, numerous specific fracture types are identified by their location or the mechanism of injury. Examples include:

- Barton’s Fracture: Affecting the distal radius and extending into the wrist joint.

- Fissure Fracture: A crack on the bone surface that doesn’t completely penetrate the bone.

- Jefferson’s Fracture: Involving the atlas, the first cervical vertebra.

- Lead Pipe Fracture: Characterized by compression and bulging on one side of the bone cortex with a slight crack on the opposite side.

- Parry Fracture/Monteggia’s Fracture: A fracture of the proximal ulna shaft coupled with radial head dislocation.

- Ping-Pong Fracture: A depressed skull fracture, typically in children, resembling an indentation in a ping-pong ball.

- Pott’s Fracture: Fracture of the distal fibula with significant injury to the tibial articulation, often involving the medial malleolus.

- Colles’ Fracture: Fracture of the distal radius with dorsal (backward) displacement. A reverse Colles’ fracture involves volar (forward) displacement.

This list is not exhaustive, highlighting the importance of a medical dictionary or coding resource for accurate interpretation of fracture documentation.

Fracture Fixation and Reduction: Restoring Bone Alignment

The primary goal of fracture treatment is to facilitate proper healing by immobilizing the bone. Casting is a common method, but surgical intervention might be necessary to reposition the bone fragments correctly. This repositioning is known as “reduction.”

- Closed Reduction: This involves manipulating the fracture externally, without surgical incision, to restore alignment.

- Open Reduction: Open reduction requires a surgical incision to access the fracture site and manually realign the bone fragments.

Coding fracture care necessitates knowing the type of reduction performed and the affected anatomical site. For instance, fractures can occur in the leg, arm, fingers, or feet, and the precise location within the bone (e.g., head or shaft of the femur) may also be relevant for coding.

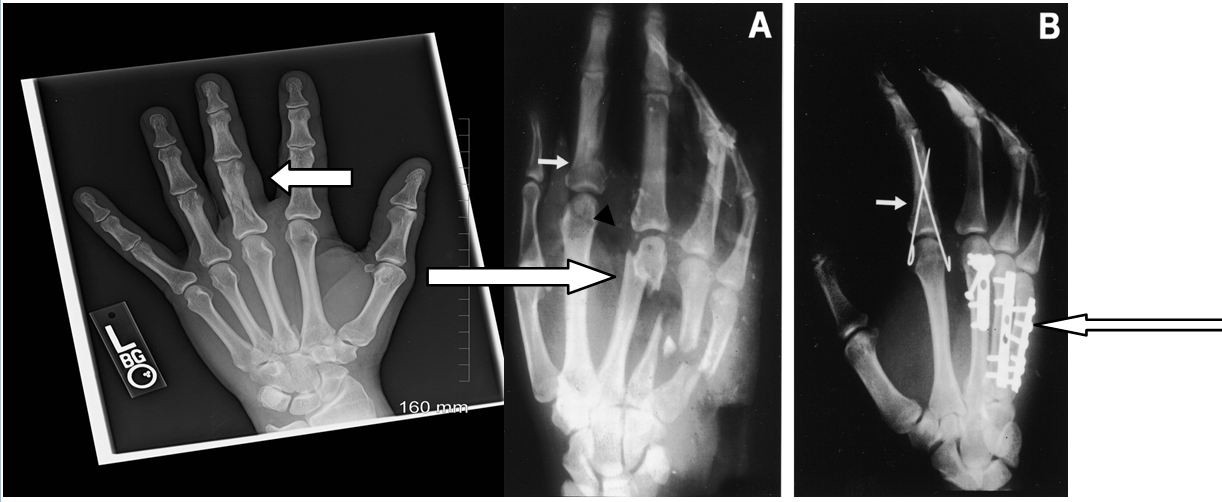

Consider the following examples illustrating different fracture types and reduction methods:

X-ray images showing different types of fractures and fracture reductions

X-ray images showing different types of fractures and fracture reductions

Image Interpretation:

- Film A (Left): The short arrow indicates a displaced fracture of the index finger’s proximal phalanx. The long arrow points to multiple metacarpal fractures in the fingers.

- Film B (Right): The short arrow shows percutaneous pin fixation of a phalangeal shaft fracture. The long arrow indicates internal fixation using plates and screws for a metacarpal fracture.

These examples demonstrate the spectrum of fracture presentations and the corresponding treatment approaches, which directly impact coding.

Billing for Fracture Care: Navigating Coding Options

When coding for non-manipulative fracture care, two main approaches are generally accepted, supported by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Medical Association (AMA):

- Fracture Global Fees: This approach bundles services within a global period.

- Alternative Method for Fracture Fees: This allows for itemized billing of services.

1. Fracture Global Fees:

According to the AAOS Guide to CPT® Coding for Orthopaedic Surgery, fracture global fees may encompass the initial hospital or office encounter in some regions. CMS guidelines may permit coding an Evaluation and Management (E/M) service with modifier -57 (Decision for surgery) if the initial visit was when the decision for surgery was made. The global period, typically 90 days from the initial fracture treatment, includes the initial cast or splint application and routine revisits (excluding physician-obtained radiographs). Recasting or splinting during the global period are usually billed separately on an “encounter” basis.

2. Alternative Method for Fracture Fees:

The alternative method is applicable when fracture treatment doesn’t primarily involve a “procedure,” such as closed treatment without manipulation. In these instances, services can be itemized as if it were a standard office encounter. Examples include undisplaced fifth metatarsal fractures, minimally displaced pelvic fractures, or vertebral compression fractures. Office, hospital, and emergency department encounters, injections, supplies, casts, splints, and treatment program necessities are coded separately as appropriate.

It’s crucial to recognize payer-specific guidelines. For office-based fracture care, payers might require appending modifier 25 (Significant, Separately Identifiable Evaluation and Management Service by the Same Physician on the Same Day of the Procedure or Other Service) to the E/M service. Practices must determine whether global fracture care coding or itemized billing is more suitable based on the specific clinical scenario and payer rules.

Coding Example 1: Closed Reduction without Manipulation vs. E/M

Reporting Closed Reduction without Manipulation:

- Cast/splint/strapping is bundled into the procedure code.

- X-rays and supplies can be reported separately.

Reporting an E/M Service:

- Cast/splint application, X-rays, and supplies can all be reported separately.

Closed reduction with manipulation procedures typically have a 90-day global period. The initial casting, splinting, and strapping, along with routine postoperative visits, are included in the global package. However, X-rays, Durable Medical Equipment (DME), and casting/splinting supplies are billed separately. Within the global period, separate E/M coding for issues related to the fracture is generally not permitted.

Example Scenario:

A patient receives closed treatment with manipulation for a fracture (CPT® code 26725). The cast application is not coded separately. Subsequent visits within the 90-day global period for routine follow-up related to the fracture are indicated using code 99024 (Postoperative follow-up visit, normally included in the surgical package…). Separate E/M coding for fracture-related issues within this period is not allowed, but casting/splinting supplies can be billed if documented.

Coding Example 2: Fractured Clavicle and Minimal Intervention

Consider a patient presenting with a non-displaced clavicle fracture. A sling is provided, and follow-up is advised only as needed (PRN). Can fracture care coding be applied in this scenario?

Fracture care codes, like other surgical procedures, typically encompass preoperative, operative, and postoperative components in reimbursement formulas. If there is no anticipated postoperative care by the treating physician, billing a fracture care code might be inappropriate. In such cases, an E/M service code might be more suitable, particularly if the treatment is provided in an emergency department setting with no planned follow-up by that physician.

Coding Example 3: Transfer of Postoperative Fracture Care

A patient undergoes fracture surgery in one location (e.g., Utah) and returns home to another state (e.g., New Jersey) for follow-up care. Ideally, the surgeon performing the surgery should bill for the preoperative (17%) and operative (63%) portions of the global fee by appending modifier 54 (Surgical care only) to the fracture care code. The postoperative care (20%) would then be billed by the orthopedist in New Jersey accepting the patient’s follow-up care, using the same surgical code with modifier 55 (Postoperative care).

However, in practice, this ideal scenario is often not realized. Communication and documentation of care transfer are essential for appropriate billing in such situations. If a transfer of care is not documented, the physician providing postoperative care may not be able to bill for it.

Essential Tools for Orthopaedic Coding

For professionals involved in orthopaedic coding, maintaining expertise and accuracy is paramount. Resources like the Certified Orthopaedic Surgery Coder (COSC™) certification demonstrate specialized knowledge. Access to current medical coding books and efficient coding search engines like AAPC Coder are invaluable for navigating the complexities of fracture care coding and ensuring compliance.

By understanding these fracture care coding guidelines from 2017, professionals can confidently approach coding and billing, ensuring accurate representation of services and appropriate reimbursement.