Introduction

Dementia Care Mapping (DCM) stands as a robust observational tool and a practice development process, playing a crucial role in enhancing the quality of formal care for individuals living with dementia for over two decades. Its evolution, driven by practitioner feedback and rigorous academic review, culminated in the eighth and latest edition published in 2005. DCM’s effectiveness hinges on trained individuals known as “mappers,” who undergo a standardized 4-day training course, licensed by the University of Bradford, that includes a competence assessment in utilizing the tool. The detailed workings of the DCM observational tool and practice development process are well-documented [3, 4]. In essence, DCM follows a five-stage cyclic process: staff briefing, mapping observations, data analysis and report preparation, feedback to staff, and action planning [5]. This systematic approach allows for a thorough evaluation and improvement of dementia care practices.

Numerous systematic reviews have evaluated DCM over the past 20 years, examining its methodological aspects and outcomes [6], research evidence [7], psychometric properties in enhancing care quality [8], and efficacy within long-term care settings [9]. While reviews of DCM’s psychometric properties have pointed out concerns regarding reliability, validity, and consistency in its implementation [7, 8], efficacy studies present varied results. Some studies indicate positive outcomes in reducing agitation, improving quality of life, decreasing falls and neuropsychiatric symptoms in care home residents with dementia, and alleviating stress and burnout among care home staff [7, 9]. However, recent randomized controlled trials in care home settings have highlighted process and implementation inconsistencies as potential factors contributing to these varied efficacy results [10–12]. This variability underscores the complexity of implementing health-based interventions and the need to understand the factors influencing their effectiveness [13].

Implementing health interventions is inherently complex, with potential challenges arising from various sources including the environment, individuals with health conditions, and healthcare professionals. Recognizing and addressing implementation barriers and facilitators is crucial before undertaking such interventions [13]. These factors typically emerge at organizational, team, and individual levels [14]. The organizational context encompasses factors like financial reimbursement, time constraints, and patient expectations. The team context involves current practices and leadership priorities. The individual context relates to staff knowledge, attitudes, competence, and understanding of the intervention [14]. Interventions targeting specific issues are generally more effective than those aiming for broad practice changes [15]. In dementia care, many interventions have shown limited impact compared to standard care. Personalized interventions, tailored to the specific needs of individuals with dementia and their families, tend to be more successful [16]. Poor intervention delivery, including protocol adherence, is a significant barrier in psychosocial interventions [16], and implementing interventions in care homes presents unique challenges [17]. Research indicates that barriers to dementia-focused interventions in care homes exist across organizational, team, and individual contexts, including lack of staff confidence, team cooperation, time, and resources [18], aligning with broader implementation challenges across disciplines [14].

Despite the established use of DCM, comprehensive summaries of evidence on its implementation processes as a practice development tool remain scarce. An edited book from 2003 [19] explored implementation aspects based on expert experiences. The 2010 British Standards Institute Publicly Available Specification (PAS 800) [4] offers implementation guidance for care provider organizations. However, formal systematic reviews in this area have been lacking. Given the importance of understanding effective DCM implementation and its barriers and facilitators for future research design and implementation, a review of this nature is essential. Therefore, this review aims to examine primary research evidence on the processes, barriers, and facilitators in implementing DCM as a practice development method within formal dementia care settings. Specifically, understanding the nuances of Dementia Care Mapping Coding within these processes is critical to maximizing DCM’s impact.

Materials and methods

This review adhered to the seven mixed-methods systematic review steps outlined by Pluye and Hong [20].

Review questions

This review sought to answer the following key questions:

- What is currently known about the implementation of DCM as a practice development intervention within formal dementia care settings?

- What are the barriers and facilitators to the successful implementation of DCM in these settings?

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included based on the following criterion: primary research study utilizing DCM as a practice development tool in formal dementia care settings that included discussion and critique of implementation processes.

Studies were excluded if they:

- Described DCM use without critiquing implementation processes.

- Used DCM solely as an outcome measure.

- Reported only on DCM’s psychometric properties.

- Were secondary research, personal views, abstracts, Master’s theses, or used DCM in non-dementia settings.

- Reported on methodological adaptations of DCM unrelated to practice development implementation processes.

Search strategies

A comprehensive search was conducted in August 2017 across PUBMED, PsycINFO, CINAHL, The Cochrane Library-Cochrane reviews, HMIC (Ovid), Web of Science, and Social Care Online using the precise phrase “Dementia Care Mapping.” This term specificity ensured the capture of relevant studies while minimizing irrelevant results, given “Dementia Care Mapping” is the tool’s standard, trademarked name. The search was limited to English language publications with no date restrictions. Reference lists of key papers and e-alerts were used to identify papers published between search completion and October 2017.

Study selection

All identified references were managed using EndNote X7 reference management software [21]. The first author screened study titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The second author verified excluded studies for agreement. Full papers of remaining studies were reviewed by the first and second authors to reach consensus on inclusion or exclusion based on the criteria.

Assessment of quality

The methodological quality of included studies was independently assessed by the second and third authors using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool [22]. This tool evaluates research study quality for systematic reviews. Two screening criteria were applied to all studies: 1) clarity of research questions/objectives, and 2) whether collected data addressed research questions/objectives. Studies meeting both criteria proceeded to methodology quality assessment, which involved four criteria per methodology type (qualitative, quantitative randomized controlled, quantitative nonrandomized, and quantitative descriptive). These criteria focused on participant recruitment, method appropriateness, researcher influence, and response rates. Mixed-methods studies had three additional criteria assessing the appropriateness of the mixed-methods approach, data integration, and consideration of limitations.

Each methodological approach within a paper received a percentage score based on met criteria (four criteria per method). Studies needed a minimum quality rating of 75% for each method used to be included.

Data extraction and analysis

Data extraction was performed using a structured table, with the standard DCM process stages serving as an a priori framework. These stages represent essential elements for a complete, successful DCM cycle. Additional extracted data not fitting under DCM stages were coded as barriers or facilitators to DCM implementation. Inductive thematic analysis was then applied to identify further key themes related to successful or unsuccessful DCM implementation. Understanding dementia care mapping coding is integral to this analysis, as the coding process directly informs the identification of these themes.

Results

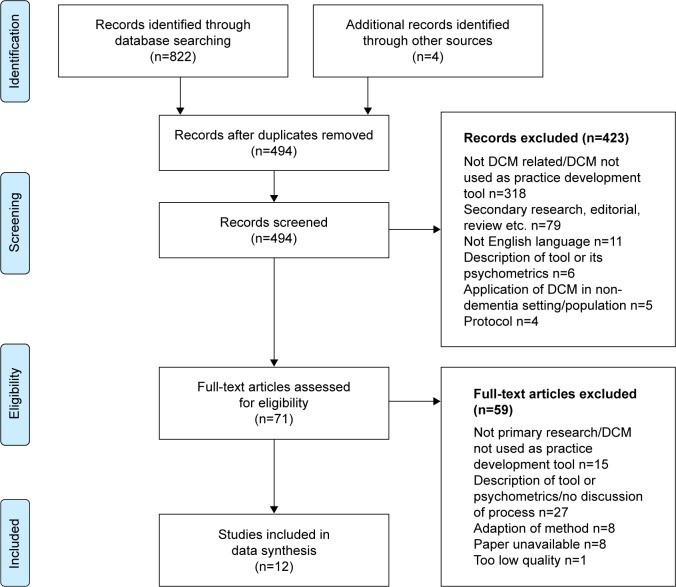

The search identified 822 papers, with four more from other sources, before duplicate removal (Figure 1). After removing 332 duplicates, 494 records were screened. Title/abstract screening excluded 423, and a further 58 were excluded post full-paper review. Thirteen papers underwent quality assessment, resulting in one more exclusion, leaving 12 papers in the final review.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Abbreviations: DCM, Dementia Care Mapping; PRISMA, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Study characteristics, design and quality

The 12 included papers originated from Australia (n=3), UK (n=2), Germany (n=3), Netherlands (n=1), New Zealand (n=1), Norway (n=1), and UK/USA (n=1), representing nine distinct research studies (Table 1). Six papers from three studies [12, 23–27] were randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental designs with control groups, evaluating DCM effectiveness as an intervention. Two studies were large-scale surveys of DCM users [28, 29], and the rest evaluated DCM implementation in single settings or organizations. Seven studies implemented DCM in care homes and two in mental health hospitals or NHS Mental Health Trusts. Seven papers reported formal evaluations of the DCM implementation process; process issues in the other five studies were identified by researchers in their discussion of DCM implementation. Formal evaluation methods included surveys [28, 29], reflective diaries [30], interviews and focus groups [25–27, 31], questionnaires, and documentary analysis [26, 27]. Five studies lacked formal DCM implementation evaluation methods; process issues were discussed in the paper’s discussion and conclusion sections based on author reflections and critiques. Quality checks indicated generally high methodological rigor, although some concerns existed regarding potential recruitment bias [12, 18, 22], acceptable response rates [20, 21], and awareness of potential researcher influence [10, 11, 17, 18, 22].

Table 1.

Overview of included studies

| Author | Country | Setting | Formal process evaluation | Methods | Mapper selection | Components of DCM process discussed | Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal/External | Mapper training | Briefing | Mapping observations | |||||

| Bone et al [34] | New Zealand | One long-term psychogeriatric hospital | No | Researcher critique | Internal | |||

| Brooker et al [32] | UK | Nine units within one mental health trust | No | Researcher critique | Internal senior staff | As soon as possible after mapping | Staff away day within 1 month | |

| Chenoweth and Jeon [23] | Australia | Three care units located within 3 care homes | No | Researcher critique | Researchers + internal staff | Within 3 days | Researchers helped unit mappers rewrite care plans | |

| Chenoweth et al [24] | Australia | Five care homes | No | Researcher critique | Researchers + internal staff | Within 24 hours | Researchers helped unit mappers rewrite care plans | |

| Dichter et al [12] | Germany | Six nursing units within six care homes | No | Researcher critique | Internal staff – crossover with other homes | Within 1 week | Within 8 weeks of mapping | |

| Douglass et al [28] | UK/USA | n/a | Yes | Survey of 161 UK and USA mappers | High satisfaction with codes Low satisfaction with time to collect data and paper/pen data collection | Low satisfaction with manual data processing | ||

| Jones et al [29] | UK | n/a | Yes | Survey of 98 UK mappers | Those working in quality, training or management roles more likely to map than clinical | |||

| Mansah et al [30] | Australia | One care home | Yes | Researcher mapper reflective diary | Researcher | Reflection permitted greater depth to analysis and deeper learning | ||

| Mork Rokstad et al [31] | Norway | Three nursing homes | Yes | One interview, seven focus groups with leaders and staff of three nursing homes | External | |||

| Quasdorf et al [26] | Germany | Six nursing units in six care homes | Yes | Interviews with leaders and nurses, documentary analysis, DCM fidelity questionnaire | Internal – crossover with other homes | |||

| Quasdorf and Bartholomeyczik [25] | Germany | Four nursing homes | Yes | 28 interviews with project coordinators, head nurses and staff nurses of four nursing homes | Internal – crossover with other homes | |||

| van de Ven et al [27] | the Netherlands | 13 units in five nursing homes | Yes | Fidelity questionnaire, documentary analysis of DCM reports, focus groups with mappers, managers and staff of five nursing homes | Internal Must have right qualities | Felt unprepared for role following training |

Abbreviations: DCM, Dementia Care Mapping; n/a, not applicable.

The results are structured around the different components of the DCM process. Understanding dementia care mapping coding is essential to interpreting these results, as the coding framework is the foundation of the observational data collected.

Mapper selection

Most studies adopted a pragmatic approach, training staff from the care setting to be mappers who then implemented DCM within the research. However, four papers across three studies [23, 24, 30, 31] involved researchers or external expert mappers leading the mapping, with limited or no input from trained care home staff mappers. In one study with trained care home mappers [12, 25, 26], a crossover approach was used, where mappers from one care home implemented DCM in another participating site. Two studies specifically evaluated aspects of mapper selection. Van de Ven et al.’s process evaluation [27] highlighted the importance of mapper personality and skills, including empathy, communication skills, holistic perspective, teamwork, group process management, and resistance management. Jones et al.’s survey [29] of UK mappers found that direct care/clinical staff were least likely to have mapped post-training (45%), while quality/training roles (100% and 82% respectively) and management roles (62%) were more likely to have mapped. Researchers also reported mapping in half of the cases.

DCM training and mapper preparedness

Only one study addressed the DCM training course and mapper preparedness post-training. Van de Ven et al.’s process evaluation [27] revealed that some mappers felt unprepared for their role despite completing both Basic User and Advanced DCM User courses. Feedback delivery was particularly anxiety-provoking. Mappers expressed a need for additional training and support for effective tool use. The authors emphasized the crucial role of recruiting mappers with the right competencies, given that even advanced training seemed insufficient. They recommended modifying the DCM training course to include more feedback delivery content and extending its length/depth to better prepare mappers, considering their diverse skill and experience levels. This highlights the importance of not just understanding dementia care mapping coding, but also the softer skills required for effective implementation.

Mapping observations

Mapper experiences during observations and DCM coding frame usage were explored in only one paper, a survey of UK and USA mappers [28]. Mappers were generally satisfied with the coding frames, although US mappers were less satisfied with personal enhancer and detractor coding. Dissatisfaction reasons were not recorded. Only 31% of US and 43.1% of UK mappers were satisfied with observation time, and 43.1% of US and 66.7% of UK mappers were satisfied with paper-and-pen data collection. These surveys predate the 2004 eighth edition of DCM, which revised personal enhancer and detractor coding [3], potentially addressing some coding concerns.

Data analysis, report writing and feedback

DCM data analysis and report writing were discussed in only one study. Douglass et al. [28] found low mapper satisfaction with manual data analysis and report generation (27.6% and 31.9% respectively) in their US and UK mapper surveys. Despite mapper concerns about feedback preparedness, feedback processes and issues were rarely discussed in the reviewed papers. Four studies [12, 23, 24, 32] reported timeframes between mapping and feedback, ranging from 24 hours to 1 week, emphasizing the need for timely feedback as per DCM guidelines [33]. A process evaluation [26] found that most participating homes delivered feedback sessions for each mapping cycle. Low staff attendance at feedback sessions in two care homes correlated with negative staff ratings of feedback usefulness and the DCM process. Staff critiques of mapper skills and DCM delivery quality suggest a link between staff engagement and mapper competence. One study [30] explored structured reflection in the mapping process, for both mapper data analysis and staff feedback and practice reflection. The author concluded that reflection deepened analysis and facilitated deeper learning through revisiting reflections and creating a shared reflective practice community among staff. This reflective process is crucial for translating dementia care mapping coding into actionable insights.

Action planning

Action planning, a critical component for practice change implementation, was also infrequently discussed. Only two studies detailed action planning approaches, ranging from staff away days within a month of feedback [32] to researcher-led care plan rewriting with mapper support [23, 24]. Another paper [12] mentioned action planning within 8 weeks of observations but lacked process details. Two studies [26, 31] analyzing DCM implementation in care homes further examined action planning. They found action planning problematic or absent in about one-third of care homes. Action plans were not developed in two sites, leading to staff disinterest in DCM participation in one site. Unachievable action plans in another site also led to negative staff ratings of process usefulness.

Facilitators of DCM implementation

Six papers [24–27, 30, 31] analyzed factors supporting mapping. Key facilitators included effective mapper-staff communication, designated DCM leadership, and management support. Quasdorf et al. [26] highlighted that strong DCM champions at team and management levels facilitated successful implementation despite barriers. Two papers explored DCM leadership in detail. Mork Rokstad et al. [31] identified transformational leadership (clear person-centered care vision) and situational leadership (unit presence, staff team knowledge) in effective DCM implementation. They also emphasized leader involvement in resident care and fostering a shared care quality responsibility culture. Quasdorf and Bartholomeyczik [25] contrasted leadership styles in successful and unsuccessful DCM implementation sites. Consistent with Mork Rokstad et al., they found strong leadership and clear person-centered care visions in successful sites. A clear organizational vision and person-centered ethos were vital for DCM success. DCM was more successful in units with dementia-friendly cultures and positive staff attitudes towards dementia care [25, 27].

Barriers to DCM

Eleven of the 12 studies discussed DCM implementation barriers. Common barriers included time constraints (training, mapping, feedback, change implementation) [23, 28, 29, 32, 34], costs (training, staff release) [24, 32, 34], lack of organizational/management support [23, 25, 27, 29, 31, 34], staff resistance to change [27, 28, 34], organizational/management changes (managerial shifts, reorganization) [25, 27], and workload/staffing pressures [25, 31]. Leadership and management approaches were the most extensively analyzed barrier. Unsupportive managers were disengaged, unenthusiastic about DCM, and indecisive, contrasting with inclusive and engaging leadership in successful sites. Staff often lacked clarity on DCM responsibility. Less supportive managers lacked a good care vision or adopted a task-focused perspective, contrasting with DCM’s person-centered approach. Van de Ven et al. [27] found that manager choice regarding DCM use impacted implementation. Managers enthusiastic about DCM and initiating research participation actively supported the process, while managers mandated to participate by their organization showed a lack of buy-in. These barriers often hinder the effective application of dementia care mapping coding in practice.

Discussion

This review reveals a significant gap in primary research evidence on DCM implementation as a practice development tool in formal dementia care settings. Only 12 research papers evaluating DCM as a practice development tool discussed implementation issues, and only seven (representing six studies) formally evaluated implementation experiences. Most DCM process components were not extensively addressed in the 12 papers. Mapper selection, training, preparedness, mapping observations, data analysis, report writing, and feedback were sparsely covered, and briefing sessions were not examined at all. However, most studies identified broad DCM implementation barriers and facilitators, aligning with individual, team, and organizational contexts in implementation science [14].

At the individual level, mapper qualities and DCM implementation leadership were frequently raised. Studies consistently emphasized that selecting individuals with the skills to implement and lead DCM is crucial for success. Essential skills included communication, empathy, and the ability to engage, work with, and lead staff teams. Mapper skill deficits led to negative staff attitudes and disengagement.

Mapper preparedness post-DCM training, closely linked to mapper selection, is underexplored. Limited evidence suggests mappers felt inadequately prepared for all DCM components, even after advanced training [27]. While mappers were generally satisfied with coding frame usage [28], complex and unstructured processes like feedback and action planning caused greater anxiety and were less likely to be completed effectively [26, 27]. This could be due to incorrect mapper selection, lacking necessary communication and leadership skills. Alternatively, the heterogeneous health and social care workforce necessitates adaptable methods and training to accommodate diverse experience, knowledge, and skill levels. Current DCM training might not adequately prepare mappers for complex process components. As recommended [27], extended and more in-depth training, alongside appropriate staff selection, is needed. However, given time constraints in DCM implementation, increasing training time and costs may be impractical. A combination of appropriate staff selection and DCM training program adjustments to enhance mapper preparedness is likely necessary.

At the team level, time availability for DCM implementation was a major barrier across all components. Survey data [29] indicated that quality or training-focused roles were more likely to map than clinical or direct care roles. This may be due to easier time allocation within their duties and possessing relevant skills and confidence. Staff shortages and service delivery pressures make it challenging for clinical/direct care staff to be released for mapping. This highlights the need to streamline dementia care mapping coding and data analysis processes to reduce time burden.

Therefore, mapper role, personal qualities, and skills are crucial considerations for DCM training selection, influencing mapping likelihood and effective DCM implementation. If less than half of trained clinical staff use DCM in practice, the cost-effectiveness of their training is questionable.

At the organizational level, time for application was a universal concern across DCM implementation, including training, mapping, and practice change. Addressing this is challenging, as poor DCM implementation, including inadequate staff engagement, poor feedback, and ineffective action plans, resulted in staff dissatisfaction and process breakdown. Effective DCM implementation requires dedicated time for each process component. Time-saving strategies, particularly for data analysis and report preparation, are needed. Electronic data collection and storage, automated data processing, and report generation could reduce mapper burden [28]. Developments include Excel-based programs and online database systems for automated reporting [35]. While currently requiring manual data input, online systems have potential for future electronic DCM data collection. Staff turnover, despite being high in health and social care [36–40], was only mentioned as a barrier in one study [26]. DCM implementation was more successful in units with stable teams. However, one unit successfully implemented DCM despite high staff turnover, attributed to a stable project coordinator leading implementation.

Leadership is the most discussed factor in DCM implementation. Effective leadership and managerial support are crucial for successful DCM cycles and sustained method use. Key leadership qualities include strong leadership for both DCM and within the implementation unit. Successful leaders were transformational, presenting a clear person-centered care vision and ethos, and situated, engaging with staff and having a strong unit presence. These findings align with studies on effective leadership in care home and healthcare culture change [41–43].

A critical finding is the need for DCM implementation in organizations already embracing a person-centered care culture. DCM appears to be a tool for supporting services already committed to person-centered care, rather than converting task-focused settings. DCM may not be suitable for all services and is likely to be effective only when adopted at the right time.

Comparing DCM to Waltz et al.’s 73 implementation strategies [44], DCM encompasses many strategies across nine clusters, including evaluative and iterative strategies, interactive assistance, and stakeholder training. However, DCM is weaker in areas like readiness assessment, barrier/facilitator identification, centralized technical assistance, contextual adaptation, organizational preparation, stakeholder engagement (including people with dementia and families), and financial support strategies. A key missing feature is organizational readiness assessment and support to establish a conducive environment for DCM success. DCM training is individual-level, expecting trained staff to lead team and organizational change to support DCM use, in addition to implementing the tool and process. This aligns with evidence that dementia intervention implementation barriers often occur at organizational or team levels, highlighting the need for support in these areas.

This review indicates that careful consideration of organizational context and readiness is essential before DCM implementation. Organizational readiness, encompassing motivation, general organizational capacities, and innovation-specific capacities [45], is critical. While DCM implementation guidelines [4] discuss organizational context, the tool and process currently lack consideration of organizational readiness assessment. Published research and implementation science theory suggest that services aiming to benefit from DCM need a pre-existing aspiration for person-centered dementia care, committed staff across all levels, strong DCM leadership, and skilled mappers with adequate time. Some studies used external mappers (researchers or expert practitioners), potentially reducing costs and staff release challenges, and ensuring skilled mapper utilization. Future research could explore different mapper selection and mapping models and the conditions needed to create supportive settings for successful DCM use. Furthermore, research should explore ways to simplify dementia care mapping coding and data analysis to reduce resource intensity.

Evidence suggests dedicating appropriate time to all DCM cycle stages, including action plan development and implementation. DCM is unlikely to resolve issues in failing services lacking leadership and person-centered care commitment. While DCM efficacy studies show varied results, implementation issues are a potential explanation. Studies with researcher-led DCM implementation showed significant positive outcomes [12], while care staff-led processes showed implementation component deficits [26, 27]. This may relate to mapper skills, preparedness, and organizational factors like time and staff release. Limited evidence suggests DCM is not a simple or quick fix solution. Services should carefully assess preparedness and commitment to change for successful and sustained DCM implementation.

Limitations

This review has limitations. Including only English publications may have excluded relevant non-English evidence. Restricting inclusion to primary research excluded practitioner experience-based publications, potentially missing valuable anecdotal insights. The review is based on a limited number of papers and studies, with even fewer formal process evaluations of DCM implementation. Findings and conclusions are based on a limited evidence base, necessitating further research to better understand effective DCM implementation components and barriers and facilitators. A randomized controlled trial with integrated process evaluation is ongoing [46], but more robust research on DCM implementation is needed.

Conclusion

Despite DCM’s 20+ years of practice and growing research, evidence on its practical application remains limited. Available evidence suggests organizational features and contexts are crucial for sustained DCM success, particularly good leadership, organizational/management support, and skilled mappers with adequate time. Further research is needed to fully understand effective DCM implementation requirements. Given DCM’s resource intensity and variable efficacy reports, potentially due to implementation variability, further research into processes and contexts for successful implementation is vital to ensure DCM investment is not wasted. Future DCM implementation studies should include detailed process evaluations to better understand implementation issues and develop mitigation strategies. This includes a deeper investigation into the role of dementia care mapping coding fidelity and its impact on overall DCM effectiveness.

Footnotes

Disclosure

CAS has conducted research on DCM and its use, including the development of the current eighth edition of the tool, and has previously been an approved DCM trainer. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.