In the landscape of clinical trials, data is the cornerstone of progress. Every piece of information generated during these trials is meticulously recorded, forming the basis for critical analyses and regulatory submissions. This data collection, often conducted across diverse global sites by numerous investigators, presents a significant challenge: ensuring uniformity and consistency in medical terminology. This is where medical coding emerges as a vital function, and a rewarding career path within clinical data management. Medical coders are the experts who process and standardize medical terms, categorizing them using specialized dictionaries to ensure accurate analysis and review. For those considering a medical coding career, understanding this process and the tools involved is paramount. This article delves into the essential processes of medical coding in clinical data management, highlighting the most widely used medical dictionaries, MedDRA and WHO-DDE, and shedding light on the common challenges encountered in this field. This exploration is intended to provide valuable insights for aspiring medical coders and anyone interested in the intricacies of clinical data management.

The Role of Medical Coding in Clinical Data Management

Clinical trials rely heavily on data collection instruments (DCIs), known as Case Report Forms (CRFs) in paper-based trials and electronic Case Report Forms (eCRFs) in web-based studies. These instruments capture a wide range of patient information, including Adverse Events (AEs), Medical History (MH), and Concomitant Medications (CM), alongside data related to the study medication itself. Multicentric clinical trials, by their nature, involve numerous trial sites across different geographical locations, bringing together investigators from diverse ethnic and professional backgrounds. This diversity, while enriching, can also lead to variations in how medical and scientific data is recorded.

To ensure that the data collected across these varied sources can be effectively analyzed and interpreted, standardization is crucial. Medical coding serves this essential purpose by applying standardized medical dictionaries to the reported data. While various data points can be subjected to coding, the coding of AEs, Serious Adverse Events (SAEs), and CM is considered mandatory in virtually all clinical trials due to their critical impact on patient safety and treatment efficacy assessment. The process of medical coding transforms potentially inconsistent verbatim terms into a structured, uniform language, enabling meaningful data aggregation, analysis, and reporting.

Essential Medical Coding Dictionaries for Professionals

The field of medical coding utilizes a range of standardized dictionaries to ensure consistency and accuracy. While several options exist, a few have become particularly prominent within the pharmaceutical and clinical research industry. Historically and currently used dictionaries include:

- COSTART – Coding Symbols for Thesaurus of Adverse Reaction Terms: An older dictionary, less frequently used now but historically significant.

- ICD9CM – International Classification of Diseases 9 Revision Clinical Modification: Primarily used for diagnostic coding in healthcare settings, less common in clinical trial adverse event coding.

- MedDRA – Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities: A globally recognized and widely used dictionary, particularly for regulatory reporting of adverse events.

- WHO-ART – World Health Organisation Adverse Reactions Terminology: Another older dictionary, largely superseded by MedDRA and WHO-DDE.

- WHO-DDE – World Health Organisation Drug Dictionary Enhanced: Essential for coding medications and understanding drug-related information in clinical trials.

Among these, MedDRA and WHO-DDE stand out as the two most extensively utilized medical coding dictionaries in clinical trials today. Their adoption is widespread due to their comprehensive nature, regulatory acceptance, and continuous updates. It’s important to note that these dictionaries are proprietary and require valid licenses for legal use. Organizations involved in medical coding must acquire the appropriate licenses, tailored to different user groups and dictionary types.

The Medical Coding Process: A Step-by-Step Guide

The journey of a verbatim term from a CRF to a coded data point involves a structured process, ensuring accuracy and consistency. This process can be broadly divided into pre-coding activities and the live project coding phase.

Pre-coding Processes

Before any coding can commence in a clinical trial, certain preparatory steps are essential. These pre-coding processes primarily involve the database programming team and the operational data management team.

Firstly, the chosen medical coding dictionary, along with any updates or revisions, must be correctly imported and loaded into the designated coding tool. In systems like Oracle Clinical (OC), the Thesaurus Management System (TMS) is commonly used for this purpose. The programming team is responsible for this technical step, ensuring that all dictionary tables and records are accurately loaded into the coding tool. This import process is typically a one-time activity for each dictionary version.

Following the import, the programming team verifies the successful loading of the dictionary by checking the integrity of tables and records within the coding tool. Once this technical validation is complete, the operational data management team undertakes User Acceptance Testing (UAT). UAT is a critical step where operational team members, who will be using the dictionary for coding, confirm that the loaded dictionary functions as expected and produces the desired outputs. This involves testing various search scenarios, auto-coding functionalities, and manual coding options.

Upon successful completion of UAT and sign-off by the operational team, the specific dictionary version is formally released for use in a particular project or study. It’s important to note that if the same dictionary version is intended for use in subsequent projects or studies, the UAT process must be repeated by the operational team members assigned to each new project or study to ensure consistent and validated coding.

Prior to assigning a dictionary to a project, several crucial points must be considered:

- Version Validation: Confirm that the latest validated version of the dictionary is available in the coding tool at the project’s initiation.

- Version Consistency Policy: Establish a clear policy regarding dictionary version usage throughout the project lifecycle. This includes deciding whether to maintain the initial version throughout the study, even if newer versions become available.

- Upgraded Version Implementation (Prospectively): Define a strategy for incorporating upgraded dictionary versions if they become available during the project. This would typically involve a prospective upgrade applied to newly collected data going forward.

- Upgraded Version Implementation (Retrospectively): Determine if retrospective upgrades will be considered, applying newer versions to data already coded with an older version. Retrospective upgrades are less common due to the complexities of recoding previously processed data.

Coding in Live Projects: Auto and Manual Coding

In the live phase of a clinical trial, medical coding is ideally performed on data that has already undergone initial cleaning and validation by data managers responsible for “Data Review and Discrepancy Management.” This ensures that the terms being coded are as accurate and complete as possible. The coding process itself primarily relies on two mechanisms: auto-coding and manual coding.

Auto Coding: This is the automated process where the system attempts to code a verbatim term directly as it is entered by the investigator on the CRF or eCRF. Auto-coding succeeds when the verbatim term exactly matches a preferred term (PT) or a low-level term (LLT) within the medical dictionary. The system automatically assigns the corresponding code, streamlining the coding process for straightforward terms.

Manual Coding: When auto-coding fails, which often occurs due to variations in terminology, misspellings, abbreviations, or terms not directly present in the dictionary, manual coding becomes necessary. In manual coding, a trained medical coder, assigned to the specific project, takes over. The coder reviews the uncoded verbatim term and utilizes their expertise and the medical dictionary to identify the most appropriate match. This involves searching within the dictionary, understanding the hierarchical structure (e.g., in MedDRA), and selecting the code that best represents the clinical concept described by the verbatim term.

It’s important to recognize that even with auto and manual coding, challenges can arise. Some verbatim terms may be ambiguous, lack sufficient detail, or represent multiple concepts combined. In such cases, the medical coder or the medical coding team initiates a query process. These queries are directed to the site investigator or medically qualified experts to seek clarification or more detailed information about the unclear term. This interaction helps the coder to gain a better understanding of the clinical context and to find the most accurate and appropriate term within the coding dictionary.

Once terms are auto-coded or manually coded, they undergo a review process by coding personnel to ensure accuracy and consistency. Unclear terms or terms with insufficient detail that were queried to the site require investigator resolution. The investigator provides updates or clarifications, and sends back a signed resolution to the data management team. Based on the investigator’s response, the data management team takes appropriate actions within the clinical trial database. The medical coder then reviews the new information provided in the investigator resolution and codes the term accordingly.

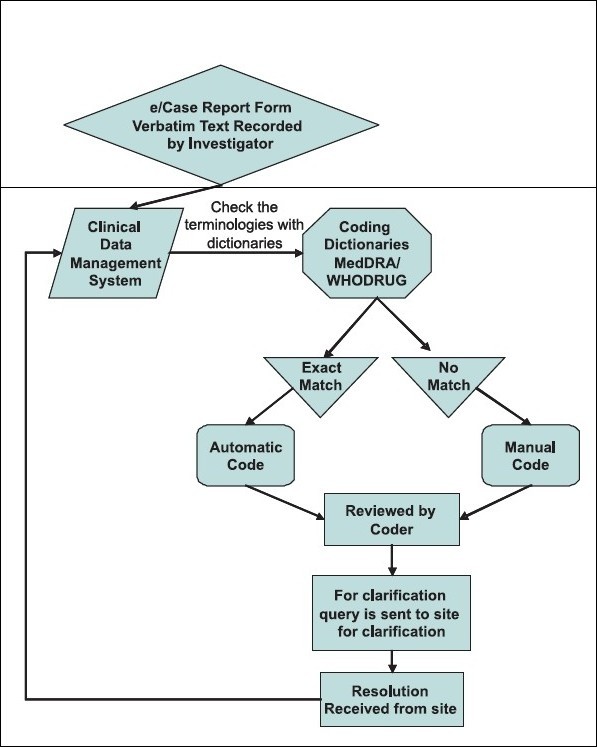

Visualizing the Coding Workflow

The medical coding process can be effectively visualized through a flowchart, as depicted below. This visual representation clarifies the steps involved from verbatim term entry to final coded term assignment.

Fig 1.

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA)

The Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA®) is a globally recognized and meticulously developed medical terminology dictionary. Maintained by the Maintenance and Support Services Organisation (MSSO), MedDRA® has gained significant prominence due to its support by the International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH). Prior to MedDRA’s development, a universally accepted medical terminology for biopharmaceutical regulatory purposes was lacking, hindering consistent data exchange and analysis across global regions.

MedDRA’s Scope and Applications

MedDRA is designed for coding a broad spectrum of medical information encountered in clinical trials and regulatory settings, excluding animal toxicology data. Its applications include:

- Coding medical terms from all phases of clinical trials.

- Representing therapeutic indications, encompassing signs, symptoms, diseases, diagnoses, prophylaxis, and functional modifications.

- Coding names and quantitative results of investigations, such as laboratory tests and imaging studies.

- Categorizing surgical procedures and medical, social, and family history information.

MedDRA is a dynamic dictionary, with two major releases annually, in March and September. Access to MedDRA terminology is obtained through an annual, renewable subscription. Each subscription ensures access to the latest updates, incorporating approved changes, additions, and enhancements to the dictionary.

MedDRA’s structure is characterized by five hierarchical levels, providing increasing granularity and specificity in medical term classification. These levels are illustrated in Figure 2 and described below.

Fig 2.

- Low Level Term (LLT): This is the most granular level of the MedDRA hierarchy. LLTs represent the specific verbatim terms as reported. Importantly, each LLT is linked to only one Preferred Term (PT).

- Preferred Term (PT): PTs are the core of MedDRA, distinctly describing a specific symptom, sign, disease, diagnosis, therapeutic indication, investigation, surgical or medical procedure, or medical, social, or family history characteristic. PTs are the terms most commonly used for data analysis and reporting.

- High Level Term (HLT): HLTs serve as superordinate descriptors for groups of related PTs. They provide a broader categorization, grouping PTs that share clinical similarities.

- High Level Group Term (HLGT): HLGTs further aggregate related HLTs. They are superordinate descriptors for one or more HLTs linked by anatomy, pathology, physiology, etiology, or function, offering an even broader clinical context.

- System Organ Class (SOC): SOCs represent the highest and most general level of the MedDRA hierarchy. They categorize terms based on etiology, manifestation site, or purpose, providing a broad anatomical or physiological classification. Examples include “Gastrointestinal disorders” or “Infections and infestations.”

Common Challenges Faced by Medical Coders

Medical coding, while essential, is not without its challenges. Medical coders frequently encounter a range of issues that require problem-solving skills and clinical understanding. Some common challenges include:

Verbatim Term Issues

- Illegible Verbatim Terms: Handwritten CRFs can sometimes contain illegible terms, making accurate coding difficult. Coders may need to consult with data managers or site personnel to decipher these terms.

- Spelling Errors: Misspellings in verbatim terms are common. Coders must be adept at recognizing and correcting these errors to find the intended term in the dictionary.

- Use of Abbreviations: Investigators may use abbreviations that are not universally recognized or are ambiguous. Coders need to understand common medical abbreviations and, when necessary, seek clarification on less common ones.

- Multiple Signs and Symptoms Recorded as Separate Events: Sometimes, investigators record individual signs and symptoms that, when considered together, point to a specific diagnosis. For instance, “running nose,” “cough,” and “fever” might collectively indicate “Pneumonia.” Coders need to recognize these scenarios and code appropriately, often to the underlying diagnosis if it is clearly implied.

- Multiple Medical Concepts Recorded Together: Verbatim terms may contain multiple medical concepts combined into a single entry. Coders must be able to dissect these terms into their constituent parts and code each concept separately for accurate representation.

- Event Recorded Without Mentioning the Site: Terms like “ulcer” recorded without specifying the location (e.g., “mouth ulcer,” “leg ulcer”) require coders to seek clarification to ensure accurate coding to the correct body site.

- Multiple Medical Concepts with Unclear Relationships: Terms describing a surgical procedure and a related injury may lack clarity regarding the cause or site of the injury. Coders need to query for details to understand the relationship between the events and code them precisely.

- Vague Medication Allergy Descriptions: When medication allergies are reported, the verbatim term might lack specifics about the allergic reaction itself or its outcome. Coders may need to query for more detail on the nature of the allergy (e.g., rash, anaphylaxis) and its resolution.

Medicinal Product Coding Challenges

Coding medicinal product terms using dictionaries like WHO-DDE also presents its own set of challenges:

- Illegible Verbatim Term, Spelling Errors, Use of Abbreviations: Similar to medical condition terms, medication names can also be illegible, misspelled, or abbreviated, requiring coders to carefully interpret and standardize them.

- Indication Prescribed is Not an Approved Indication: Investigators may record the indication for which a medication is prescribed. If this indication is not an approved indication listed in the prescribing information, it can complicate coding and require careful consideration of the context.

- Local Brand Available, Generic/Active Ingredient Unknown: In multicentric trials, local brands of medications may be reported. If the generic name or active ingredient is not provided, coders need to research and identify the correct active ingredient for accurate coding in WHO-DDE.

- Multiple Medications Recorded Together: Similar to medical condition terms, multiple medications might be listed together in a single verbatim term. Coders must separate these into individual medication entries for proper coding.

WHO-DDE: Another Vital Dictionary for Drug Information

The World Health Organisation Drug Dictionary Enhanced (WHO-DDE) is an indispensable resource for medical coders, particularly for coding medication data in clinical trials. Maintained and updated by the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC), WHO-DDE is recognized as the most comprehensive dictionary for medicinal product information globally. It is used by drug regulatory authorities, pharmaceutical companies, and contract research organizations (CROs) worldwide. The dictionary covers proprietary and non-proprietary medicinal product names from over 90 countries.

WHO-DDE has evolved over time, and currently encompasses three distinct dictionary types:

- WHO Drug Dictionary (WHO-DD): The original and foundational WHO drug dictionary.

- WHO Drug Dictionary Enhanced (WHO-DDE): An expanded and enhanced version of WHO-DD, offering greater detail and coverage.

- WHO Herbal Dictionary (WHO-HD): A specialized dictionary focusing exclusively on herbal medicinal products.

WHO-DD and WHO-DDE primarily contain information on conventional medicinal products, but also include other product types such as:

- Medicinal products (pharmaceutical drugs)

- Herbal remedies

- Vaccines

- Dietary supplements

- Radio-pharmaceuticals

- Blood products

- Diagnostic agents

- Homeopathic remedies

The WHO Herbal Dictionary, introduced in 2005, specifically catalogs herbal entries. It utilizes the Herbal Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (HATC) classification system for herbal product categorization.

A key feature of WHO-DDE is the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system, an integral part of the dictionary. ATC classification categorizes medicinal products based on their main therapeutic use, following a five-level hierarchical structure:

LEVEL 1: Anatomical main group (e.g., Cardiovascular system)

LEVEL 2: Therapeutic subgroup (e.g., Antihypertensives)

LEVEL 3: Pharmacological subgroup (e.g., Beta blocking agents)

LEVEL 4: Chemical subgroup (e.g., Selective beta-1-receptor blocking agents)

LEVEL 5: Chemical substance (e.g., Metoprolol)

For example, the ATC classification for the widely used medication Metformin (for diabetes) is:

A – Alimentary tract and metabolism

A10 – Antidiabetics

A10B – Blood glucose lowering drugs, excl. insulins

A10BA – Biguanides

A10BA02 – Metformin

This structured classification system within WHO-DDE allows medical coders to not only identify and code medications accurately but also to understand their therapeutic context and pharmacological properties, enhancing the depth and utility of coded medication data in clinical trials.

Conclusion

Medical coding is an indispensable process within clinical data management, ensuring the standardization and uniformity of medical terminology in clinical trials. It is a crucial step in transforming raw, varied verbatim terms into analyzable data, ultimately supporting robust data analysis and reliable research outcomes. For individuals seeking a detail-oriented and impactful career, medical coding offers a specialized path within the growing field of clinical research. A deep understanding of medical coding processes and proficiency in utilizing essential dictionaries like MedDRA and WHO-DDE are fundamental skills for success in this career. As clinical trials become increasingly global and data-driven, the role of skilled medical coders will only continue to grow in importance, making it a vital and rewarding profession within the healthcare and pharmaceutical industries.